Limits of Potential – The Rational Quantification of Personal Potential

By framing people’s psychometric traits against their actual performance, it becomes possible to draw conclusions based on facts rather than mere subjective impressions. One of the most widespread myths of self-help spirituality is the idea of unlimited potential supposedly hidden within every person, which is said to be unlocked by reaching the “right level of consciousness.” Approaches such as “effortless creation” and “quantum leaps in self-development” often turn out to be oxymorons comparable to concepts like “business constellations”: their effects are not only unproven but frequently directly harmful to genuine personal development. Such narratives create the illusion of growth without discipline, effort, or responsibility.

The Three Dimensions of Potential

This analysis is based on an objective understanding of three fundamental components or rather aspects of human potential. First, there is biological potential — a psychometrically measurable, largely innate cognitive, temperamental, and neurobiological foundation that sets real limits and possibilities for the individual.

Second, there is situational potential — the extent to which this biological base can actually be realized within a given social, economic, and institutional environment.

Third, there is moral potential, which is rarely discussed because it requires honesty and a willingness to endure discomfort. At its core lies the Latin concept of passio — suffering. Moral development entails a readiness to bear responsibility, tolerate tension, abandon easy solutions, and voluntarily take on burdens that ideologies of comfort seek to avoid. It is often this third dimension that determines whether a person’s potential remains a theoretical possibility or becomes a lived reality. The following sections will explore these aspects in greater detail.

The Myth of Unlimited Personal Potential

It is true that Viktor Frankl already described in his book Man’s Search for Meaning how people were able, even under the most extreme conditions, to find within themselves the inner strength to cope and survive. Numerous studies of children and parents who have had to face death in highly adverse circumstances likewise demonstrate how remarkable human resilience can be in the face of existential trials.

Yet many spiritual “creative teachings” about how to achieve or “manifest” financial freedom — especially when they emphasize its supposed ease — ultimately work directly against this very concept. They distort the ideas of resilience and meaning-making by turning them into simplified recipes for success.

In most Western self-help and mystical practices that link spirituality with financial achievement, a myth is embedded: the belief in unlimited potential hidden within the individual, supposedly unlocked through the right practices or forms of self-regulation. In reality, the situation can be approached in a far more pragmatic way.

Because “potential” as a concept is inherently highly abstract, it can easily be mystified and monetized through the sale of so-called “activation techniques.” It is precisely this abstraction that makes potential an ideal commodity.

From a transactional perspective, the exchange is simple: a person pays money — and interestingly, many practitioners of spiritual techniques operate here on thoroughly capitalist principles — and in return receives the promise of quantitative, sometimes even exponential or “logarithmic,” growth that is said to already exist within them.

In essence, people are sold something that they are told they can then activate within themselves in unlimited form and monetize in a free-market environment. The promise does not lie in providing skills, knowledge, or structured development, but in the idea of a hidden inner treasure that merely needs to be accessed. It is precisely here that the first fundamental problem of such practices becomes apparent — one link in a longer chain of problems that we will examine next.

Quantifying Biological Base Potential – Mental Ability, Industriousness, and Extraversion

In order to begin quantifying an individual’s personal potential at all, one must first conceptualize it. From a pragmatic perspective, maximum personal potential can be understood as a combination of personality traits consisting of three fundamental components that are approximately 50–60% inherited (and often, in the final analysis, to an even greater extent).

In simplified terms, these are: mental ability, industriousness, and certain components related to extraversion.

As an additional factor, biological age may also be considered in quantification, because the higher it is, the more limited the opportunities become for long-term attempts at achieving economic independence. If time is lacking, then it is simply lacking. The world knows very few people who have achieved major economic “quantum leaps” in their nineties.

GMA – General Mental Ability

Let us examine the components of theoretical total potential separately. The first is general mental ability (GMA), which is expressed primarily through IQ.

Contrary to popular-scientific and commercialized spirituality, there are no scientifically distinguishable “different forms of IQ.” People who have taken IQ tests multiple times during their lives and received average or below-average results — or who have received sufficient confirmation from life that thinking is not their strongest suit — often tend to emphasize the superiority of emotional intelligence or “street smarts.”

The problem is that these concepts cannot be compared on the same basis. It is like trying to objectively compare the speed of a racehorse with that of a mythical unicorn. Simply put: the latter does not exist.

It is precisely the abstraction and arbitrary use of such terms that makes it possible to successfully commercialize what cannot be quantified. This allows extensive discussion about “developing” something that does not exist in scientifically defined form, but around which a business model can be built.

IQ is extremely rigid and becomes exceptionally stable after early adolescence. From a certain point onward, it inevitably begins to decline. There are scientifically supported ways to slow this decline — primarily regular physical activity, avoidance of addictions, and thoughtful nutrition — but there is no scientific consensus on any method that would meaningfully increase IQ.

Put bluntly: if it is not there, you cannot add it later.

A person can change their appearance, undergo cosmetic surgery, lose weight, or even surgically increase their height, but their cognitive base in the IQ sense remains largely fixed. Psychometrically, IQ correlates strongly with openness to ideas — curiosity, the desire to read complex texts, to think conceptually, to seek solutions to difficult problems, and to analyze patterns in behavior and phenomena. This, too, is well established scientifically.

Industriousness

The second component of innate potential is biological industriousness.

Contrary to popular myths that portray achievement as “easy,” a person’s internal drive to work, be productive, and use time purposefully is largely innate. Behavioral genetic studies show that its heritability often exceeds 50%.

The stronger a person’s inner drive to work, and the more structured and disciplined its expression, the greater their potential to achieve something significant professionally.

Popular culture sometimes promotes the idea of “lazy genius” — the myth that people with low industriousness are especially creative — but such constructions lack scientific support. Innovation and creative problem-solving correlate more strongly with openness to ideas than with low work drive.

Low industriousness does not manifest as “brilliant laziness,” but as a preference for easier, often immediately rewarding activities over important and more complex tasks. Spiritual narratives often romanticize “being,” tranquility, and the avoidance of effort, portraying work as aggressive self-imposition. In practice, this conflicts with real achievement behavior.

Economic success correlates strongly with a person’s ability and willingness to work consistently over long periods. The same pattern repeats within organizations: positions with greater responsibility, compensation, and opportunity are attained by those who contribute systematically more.

If a person feels an internal drive to work, for example, 80 hours per week, their potential is, ceteris paribus, significantly greater than that of someone who works 40 hours. This is not a recommendation, but an empirical observation.

It is important to distinguish between inner industriousness and its realization in effective working hours. The former is usually a prerequisite for the latter and often enables compensation for deficits in other traits.

Assertiveness and Low Agreeableness

The third component of base potential is innate extraversion, assertiveness, low agreeableness, competitiveness, and directness.

Although Western spirituality often idealizes “win-win” harmony, data show that higher levels of assertiveness are associated with greater economic success potential — especially when accompanied by enthusiasm and sustained focus.

Here, too, myths circulate about “waiting for the right state,” energies, and levels of consciousness. In practice, things function much more simply: when a person has an innate need for self-assertion and enthusiasm, they act methodically and consistently, regardless of their internal “mood.”

This applies both to creative work and to more mechanistic intellectual activities. It is a fundamental catalyst that largely determines the level of biological base potential.

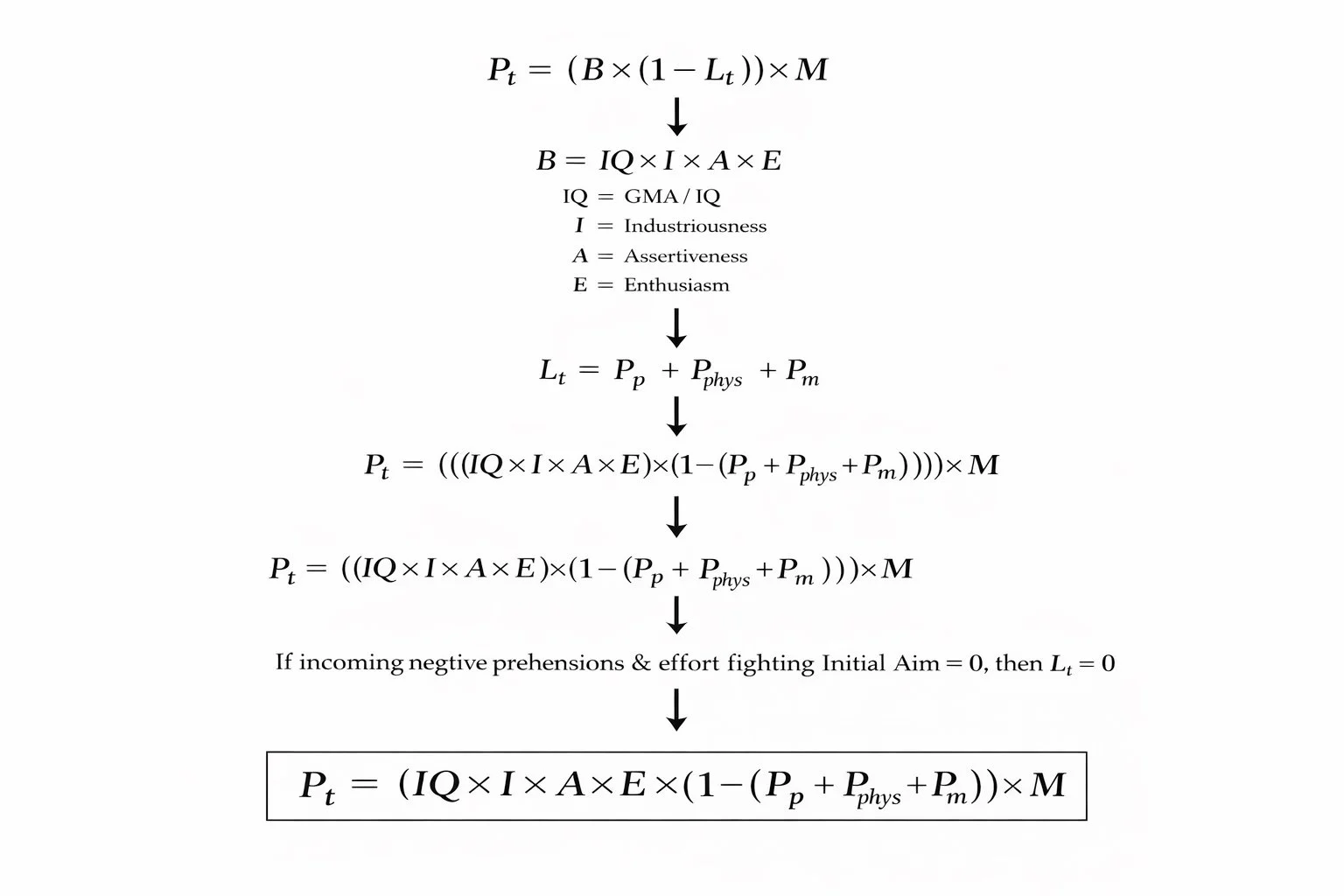

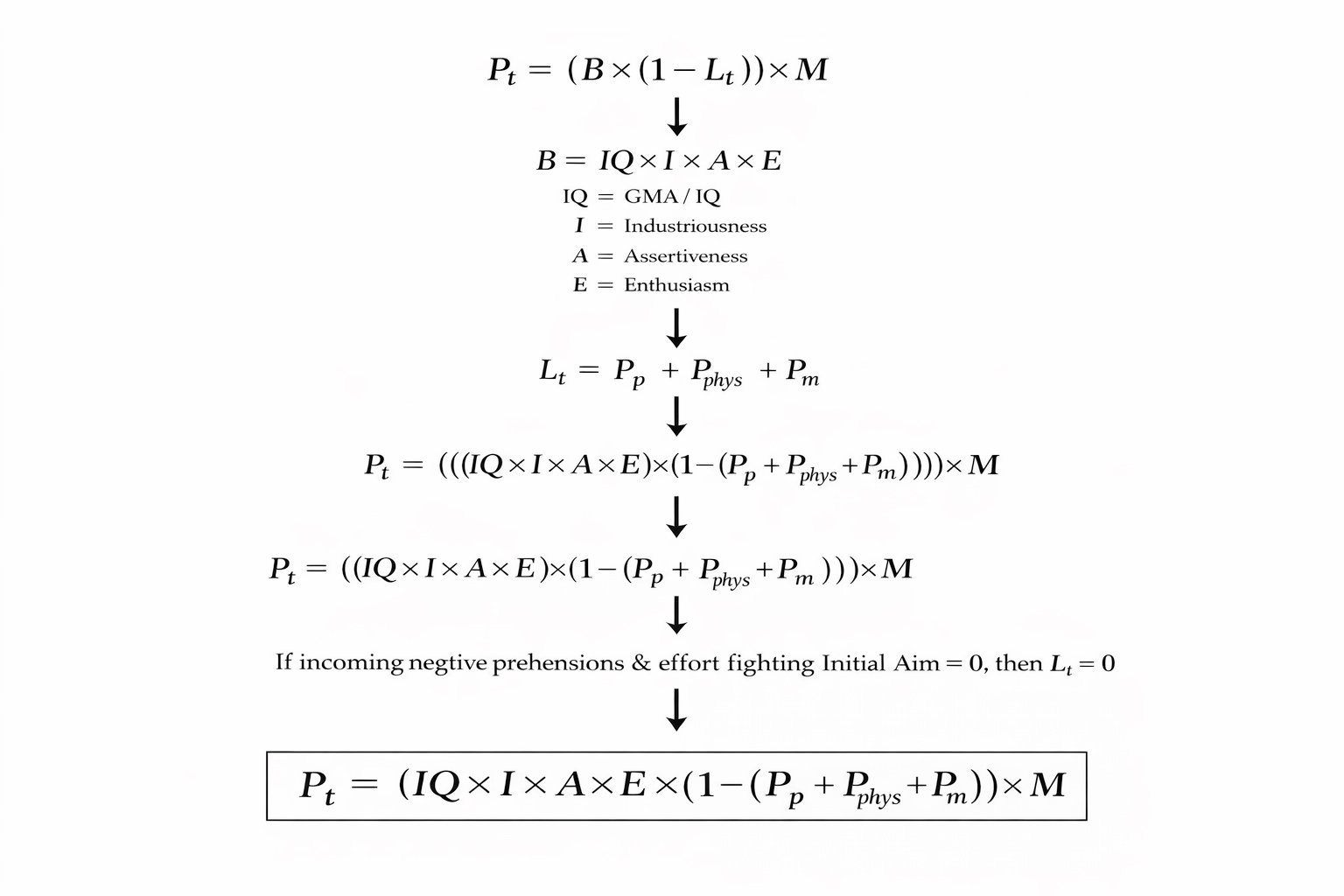

The Integrated Base Potential Model

Base potential can be quantified through three core components: intellect, industriousness, and assertiveness.

Through their interaction, an individual starting point emerges that determines the initial level of potential and serves as the baseline value in subsequent developmental processes.

Situational Momentary Potential – Process Theory and the Soldiers Metaphor

If we take the previously described personal potential as a baseline and express it conditionally as 100 units, we may imagine it as a unit going into battle with one hundred soldiers.

To better understand a person’s momentary potential, it is useful to examine the situation through the lens of process philosophy (A. N. Whitehead). Each moment (actual occasion) is formed through causal chains from previous moments, through the physical and psychological inputs of the present moment, and through the moral orientation that Whitehead calls the initial aim.

When quantifying momentary potential, it is important to understand that none of these components increases base potential — they can only reduce it.õ If unresolved conflicts, trauma, real constraints, or mental blockages are carried over from the past and must be pushed to the margins of consciousness, this immediately consumes part of one’s potential. Figuratively speaking: some soldiers have already fallen before the battle even begins.

The same applies to the physical and social environment. Positive thinking does not change objective conditions. If a person is imprisoned, they do not “think” themselves out of solitary confinement. If this example seems extreme, the same allegory can be applied, for instance, to a single mother with two or more small children. If someone believes that this is mentally far less exhausting than isolation, they should try both in order to form an objective judgment — and it is by no means certain that, at certain moments, imprisonment would not even be preferred.

The idea here is simple: momentary potential is determined by historical, physical, mental, and moral inputs. If a person is in constant financial and emotional overload, so exhausted that they lack even the energy to think about the future, then most of their “soldiers” have already fallen.

If we assume that the most capable individuals have, on the basis of their personal traits, a maximum of 100 soldiers, and even for them the number entering battle at any given moment is 100–X, then for a person with more modest innate abilities the initial number may already be as low as 10–20. Considering psychometric distributions, this comparison is in fact generous. If we take exceptionally capable individuals — so-called “Elon Musks” — as the 100-unit reference, most people’s baseline potential is even lower.

When additional physical, psychological, and situational constraints are added, the number of “soldiers” entering battle may sometimes shrink to only a few.

In such circumstances, exhortations addressed to the individual —

“Use your potential.”

“Rise to a higher level of consciousness.”

“Start creating.”

“Open yourself.”

“Manifest.”

“Notice opportunities.”

— inevitably sound like empty rhetoric.

A person may sincerely try. They send their few remaining soldiers into battle. But their number remains small — regardless of effort or belief.

The Battlefield and the Harsh Reality of Capitalism

If we consider what this “war” is into which people send their “soldiers” of potential in order to earn money, it is inevitably the global competition on the battlefield of value creation.

Earning money is neither an art nor a matter of chance. It is — and has always been — a function of value creation.

What kind of value can a person with limited potential create, even if they act with good intentions and within their abilities? The upper limit of their value creation corresponds to what they are able to achieve with their “soldiers” at any given moment.

At the same time, in a capitalist society, they face competition from all others whose potential to create value is significantly greater. This is not a judgment, but a pragmatic fact.

For this reason, individuals with the lowest momentary potential tend to work in occupations where the added value created is minimal. This may include work as a food courier or in other roles that can be learned in a few hours or days. One can become a competent food courier with a few hours of preparation, or a provider of certain beauty services within a few weeks.

These may serve as useful entry points into the labor market, but from the perspective of economic independence, the value created through such work is usually very tightly constrained.

The reason lies in low entry barriers. When almost anyone can offer the same service, no sustainable added value emerges that could be monetized at a higher level. Consequently, a person’s real capacity to make “quantum leaps” in earning power at any given moment is largely predetermined. Claims that this capacity can be rapidly and quantitatively increased through specific techniques are generally highly tendentious.

It is precisely this limitation, combined with the hope for quick solutions, that creates fertile ground for the sale of spiritual self-development techniques. The promise of bypassing structural constraints is always commercially attractive.

The greatest value is created by individuals who possess rare skills, deep specialization, high intellectual capacity, extensive knowledge, and long-term experience. In most cases, they have invested a large portion of their lives in developing these attributes.

One of the most uncomfortable aspects of capitalist competition is that in every field one must compete with people of this profile. Doing so requires very high competence, extraordinary industriousness, and an inner readiness for conflict and confrontation. The same mechanism operates within organizations. There, too, those who create the most value tend to move upward. All of this constitutes the technical side of goal realization. However, the selection of goals themselves depends on value hierarchies. These hierarchies determine what kind of success a person pursues in the long term and what price they are willing to pay for it.

Long-Term Success as the Result of Moral Choices

When potential is viewed from the perspective of achieving lasting success, it cannot be treated merely as a technical, quantifiable formula. It must be understood as the application of that formula within a proper moral framework. This is precisely why, in recent years, it has become increasingly clear that many problems previously regarded as technical are, in essence, moral.

What does this mean more precisely?

The realization of potential for achieving long-term and sustainable economic well-being is possible only when value creation functions both in short-term client relationships and at the broader societal level over time. This transforms the pursuit of economic freedom into not only a matter of skills and resources, but also one of moral responsibility.

Most leaders do not lose their own or their organization’s success because of limitations in potential, but because of moral relativism. For this reason, there is a strong correlation between the clarity of value hierarchies and long-term organizational success.

Although this is not new knowledge from a human resources perspective, employee engagement and willingness to exert effort are most strongly influenced by the relationship with one’s direct supervisor. Discussions of problems in this relationship usually focus on excessive or insufficient intervention, lack of feedback, or communication issues.

Much less frequently is attention given to the underlying core of the problem: divergence in internal value hierarchies, especially in situations involving morally significant decisions that inevitably reduce to defining “good” and “evil.”

A leader’s moral values are expressed in their value hierarchy. If this hierarchy is less aligned with the general logic of life and with the employee’s values, the working relationship inevitably becomes temporary. Rhetoric and motivational speeches cannot compensate for this. What matters is the person’s internal moral structure.

This typically becomes evident precisely in situations where value structures become visible — today often through digital traces.

Moral Relativism and Vulnerability

In summary, the most dangerous and vulnerable combination is low potential for economic success combined with moral relativism. One example may be a single mother with limited cognitive capacity whose marriage has collapsed due to her own infidelity. If, as a result of moral relativism, she later engages in conflicts over children or property, she typically loses both, and eventually her only options may be low-paying work or some form of prostitution (OnlyFans, travel-related prostitution, lingam or yoni massage, intimately servicing “sugar daddies” in exchange for car leasing, and similar arrangements).

One might say, “People should be understood as acting within their abilities,” but this is neither sufficient nor fully correct. Morality and moral absolutes are not privileges of the intellectually gifted. Honesty, morality, axiological boundaries, and disciplined passion that does not descend into recklessness are in fact closely interconnected.

Passio and the Moral Multiplier

It is often said that “people should be understood within the limits of their abilities.” This is partly true, but insufficient. Morality and moral absolutes are not privileges of the intellectually superior.

Honesty, responsibility, axiological boundaries, and disciplined passion are closely related.

A common belief holds that a fulfilling life is based on effortless joy, enthusiasm, and “being in flow.” In reality, the deeper source of passion is connected to the Latin concept of passio — suffering, endurance, inner effort.

Passio signifies the ability to bear the inevitable pain of life without the collapse of identity. It is the force that allows a person to remain on a meaningful path even when it is uncomfortable.

If there is one central idea in this work, it is the following:

A person’s innate and situational potential is multiplied by their moral potential.

Moral potential functions as a multiplier.

It begins with honesty toward oneself and expands into honesty in all actions and words. The passion for achievement is not euphoria, but a form of sincere suffering — a willingness to live a harder but more meaningful life.

Moral potential can significantly amplify a person’s actual capabilities. At the same time, its activation is uncomfortable, because truth is often, especially at the beginning, more than one can bear. It destroys the old identity before a new one can emerge.

There is also an important limitation: the moral multiplier cannot compensate for a nonexistent base. Zero multiplied by infinity remains zero.

Conclusion

Developing moral potential is a complex and long-term process. It offers no quick solutions and no psychological comfort. It is worth pursuing not only for success, but in order to become a better human being. This is what ultimately creates the foundation for a lasting, dignified, and internally stable life.