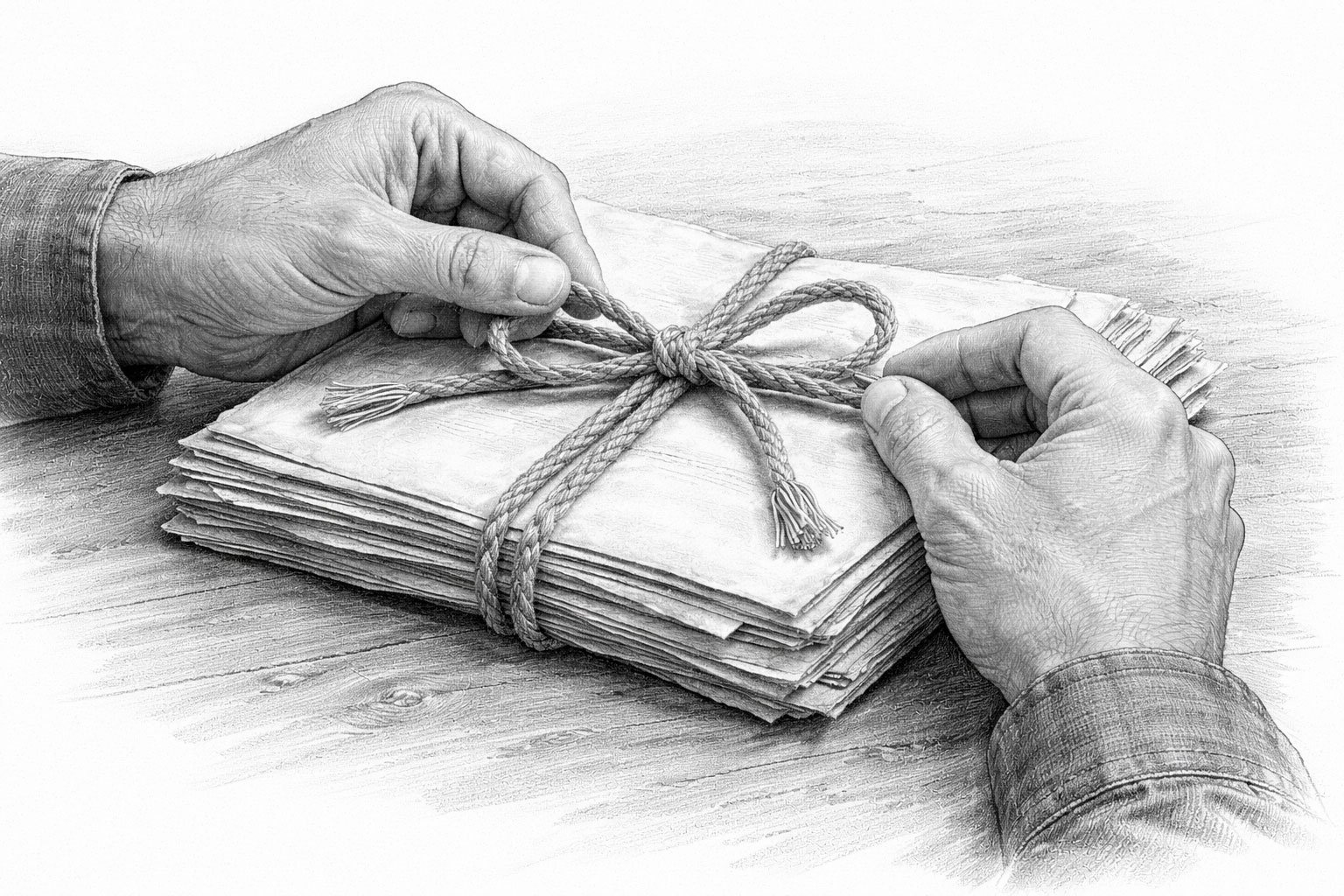

50 and tying up loose ends

“When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” ( 1 Corinthians 13:11) In work and training settings, the significance of inevitable death in making sense of life’s meaning has, in recent times, become increasingly apparent. This is a warmly paradoxical and thoroughly welcome development, despite the fact that most people are afraid to think about it.

The ultimate necessity of death in achieving meaning

I remember that when I once read The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker, I was, on an intuitive level, largely in agreement with him — yet inwardly a resistance was growing, the precise nature of which I did not yet understand at the time. Over the years (roughly 2010–2025), I came to see more clearly what had been troubling me.

Becker approaches the moral dimension of religion and culture primarily in instrumental terms: as systems that help human beings cope with the awareness of their inevitable mortality. According to him, dogmatism, normativity, and prescriptive moral frameworks enable attention to be diverted away from the direct awareness of death, offering a form of symbolic “immortality” through meaning, roles, and collective narratives. Within this framework, religion becomes one mechanism among many through which human beings regulate existential anxiety.

It is precisely here that, in my assessment, a categorical problem emerges in Becker’s analysis—at the level of the hierarchy of importance. He treats the fear of death as primary and interprets the meaning of religion as a psychological function derived from that fear, leaving open—but in practice setting aside—the possibility that religion’s central role may not be merely regulatory or compensatory. Instead, it may be fundamentally descriptive: pointing toward something that gives life meaning independently of the psychology of death anxiety.

What does this mean in the simplest terms? Above all, it means that death is not necessarily the source of fear, nor merely the partially conscious ultimate object of anxiety. Rather, thinking about death in this way — and fearing it in this way — is itself a symptom: a sign that something more meaningful is missing from a person’s life. At the moment when a person senses or discovers something that is more important than death, death itself becomes, at the level of ideas, instrumental—it enters into the service of something greater.

This is precisely what happens when a person has formed a value system in which the primary aim is not the avoidance of fear, but the substantive meaningfulness of life. Living a life in such a way that it contains something that makes it genuinely meaningful would be impossible if that life were to last forever. This paradox is rarely recognized. Without finitude, responsibility would disappear: everything could always be postponed, everything repeated endlessly, and nothing would ultimately carry weight. Paradoxically, such a life would not be pleasurable but would become unbearably torturous.

For this reason, fixed value systems — especially those organized according to a clear vertical hierarchy — have increasingly come to represent, for many, a way of understanding life in which death is not an enemy but an instrumentally necessary condition. It is precisely through death that the remaining life acquires weight and value through temporality.

When a person is free to think of death as something that ennobles life and makes meaning possible, they may experience, instead of fear of death, a different and constructive fear: the fear that, within the time that remains, one will fail to realize oneself in a sufficiently meaningful way.

Fifty years as a meaningful boundary

Having lived most of my life observing, from the side, the life trajectories of people in my closer circle older than myself, I cannot ignore the rapidly approaching milestone of my own fifty years. It is a point in time whose anticipatory quality differs markedly from many other anniversaries. In Martin Heidegger’s sense, anticipation (Vorlaufen) around this age no longer remains an abstract philosophical possibility, but becomes an existential and ontologically immediate reality.

As he formulates it in Being and Time: “Death is the utmost, ownmost, nonrelational, and unsurpassable possibility of Dasein.” At this stage, death can no longer simply be ignored or intellectually neutralized. In dealing with the thought of death at this age, two fundamentally different approaches tend to emerge. Since a significant proportion of my consultation clients have already crossed this threshold, many of them are able, in retrospect, to see clearly which stance they adopted in their lives before and after it. The distinguishing factor proves to be precisely the presence — or absence — of a vertical structure grounded in a monotheistic core value.

When a meaningful value system is present, a person reaches a certain kind of peace around the age of fifty — not through comfort, but through clarity. They come to understand the weight of time already spent and time still remaining, and they can clearly distinguish between time consumed by activities of little significance and short-term perspective (living for the moment, chasing pleasures, seeking happiness as an end in itself, adventurous and self-centered living) and time that has been invested meaningfully. Such meaningful investment typically takes the form of assuming responsibility for family, children, and home, or even — let us be honest, often to a rather limited extent, and yet parts of this cannot be dismissed outright — an attempt to make the world better in some way. Fifty is the age at which such a person understands that it is now time to begin tying up loose ends. One must become extremely critical about what is still realistically possible, because time is finite, and it is precisely this limit that demands focus. Awareness of the inevitability of death becomes liberating only when there exists an inner recognition that life has been, and continues to be, meaningful.

In the absence of a meaningful value system, however, the fiftieth year strikes a person like a cartoon scene in which a frying pan flies into the character’s face: a moment of paralysis, followed by chaotic flailing. There are many such men as well. Here, fear of death does not bring peace or clarity, but activates mechanisms opposed to them. What begins to dominate is intense suppression, applied with such frequency that the thought of death is eventually pushed even to the margins of consciousness — partly already in the sense of pathological repression. Typical expressions from such men include: “half of life is still ahead,” “I’m in better physical shape than ever,” “everything is possible.” Even a child can sense that this is a pitiable clinging to lost youth and an attempt to deny reality — especially in relation to the approach of death.

This is poorly concealed fear of death, which drives a person either into dissolving and soothing pseudo-spirituality or, in more tragic cases, into the Sugar Daddy role. In the latter case, a partner several decades younger is acquired, one who effectively sells her body in exchange for, for example, a car lease or the financing of a lifestyle, thereby prolonging the aging man’s illusion of eternal youth. Such women often only partially realize that, in doing so, they are trading away their dignity and the possibility of a meaningful life for small change — but that, unfortunately, is how it is, because time is merciless.

The weight of time

The weight of time appears to be an impossible concept for all those who have not understood that death is far from the most unpleasant thing in life. It is precisely in this respect that Irvin Yalom balances Ernest Becker in my view—with calm, sobering rationality. When, in my youth, I read all of Yalom’s books, I came to understand through him—much as several of my lecturers had said before, though without the same impact—that dynamic therapeutic interventions can be not only theoretically facinating, but at times surprisingly practical.

Speaking of meaninglessness as one of the existential fears, Yalom has repeatedly stated: “Death will take us, but the idea of death can save us.” This very thought — that looking honestly, sincerely, and respectfully at death may help us live, or sometimes finally begin to live at all — is not merely comforting, but potentially salvific. Here we arrive at a notion that is difficult to prove physically (I admit this openly), yet by no means impossible: the different weight of time. In practice, time acquires weight precisely through the inevitability of death — ideally not its too-imminent arrival. In this sense, time can, in a way, be “weighed.”

I believe Alfred North Whitehead even offered a philosophically and scientifically serious framework for this. In Process and Reality, he describes how each new moment gathers into itself the experiential and event-based impact of chains of prior moments. Every subsequent moment carries within it the reality of those that preceded it. For example, if, within these moments, children are physically present — children whom one has seen from their very birth — then in each such moment that same child is present in all their previous ages, as they have been since birth. When these moments take place at home, the home is no longer merely a physical environment but rather — in the sense articulated by Kjell Westö — a living environment: almost a living entity in its own right, bearing within it the accumulation of temporal layers, the moral weight of memory, and the traces of repeated togetherness, shared suffering, tenderness, and the morning clarity of realizing that, despite everything, all are still alive and well.

All of this is carried forward into the togetherness of subsequent moments. The temporal weight of such moments is qualitatively something entirely different from the temporal weight characteristic of entertainment, the pursuit of a constantly varied life, or hours spent in solitude. Such hours are wasted time, and people know this while they are living through them; for this reason, even the attempt to shape oneself into a happy person cannot truly succeed in producing genuine happiness.

Everyday disappointments, quarrels, joys, laughter, sadness, and nostalgia; learning something new; resolving conflicts; “passing judgment” and helping others (such as children) make sense of life — these are moments whose meaningful charge is immense. Happy are those who realize this in time, because time is merciless, and life always defeats the individual — most often decisively and with ease.

Nodes in time and living in the clouds

In the course of my studies, I have read a great deal of Slavoj Žižek and Jacques Lacan, and — like many who initially fall in love with them — I later became disappointed, and eventually learned to appreciate the considerable good and, in a certain sense, the genius present in their work. This is so despite fundamental differences in worldview — and that, too, is a skill that tends to come with age.

One of the central concepts in their thinking is the Real: not “reality” in the everyday sense, but the moment when a person encounters something that no longer submits to symbolic ordering or narrative beautification. This experience is always immediate only in retrospect, yet it is unmistakable as a confrontation with the essential reality of life in its most direct sense. It is precisely from such moments that chains of future moments begin — chains that unfold inevitably over long stretches of time, often until death (or until the next nodal point of comparable existential weight).

The most meaningful of these nodal points are those that concern children: from the idea of conceiving a child (or, in the best sense, allowing it to happen), to the birth of the child, to giving a child a home, and finally to winning the right to be a parent in the child’s everyday “grayish ordinary routine.” Of these life-nodes, I consider the last to be by far the most meaningful.

All parents who have fought for — and won — a place in their child’s routine daily life know that there is, in truth, nothing gray about this repeated everydayness. It is the present day - this day - that binds past and future together and generates an intense sense of being alive.

In practice, at the threshold of the fiftieth year, for the vast majority of those who have arrived at a meaningful life, these moments are directly connected with children and family. No matter how one interprets or allocates daily life temporally, it is difficult to conclude that family and children would account for less than half of meaningfulness as a whole (that is, at least half consisting of children and family, with everything else combined making up the remainder). Over time, this distribution tends to tilt even more clearly in their favor — especially through the realization of how decisive it is to invest time in shaping children through direct personal example.

At this point, one might assume that such talk amounts to “living in the clouds” and carries little practical weight. Yet such criticism more often reveals the critic’s own developmental room for growth in psychological maturity, and the logic here works in the opposite direction. The more a person has understood the usefulness—and even the necessity — of facing death directly, the clearer it becomes what genuine “living in the clouds” actually means.

So-called drifting into the clouds most often manifests as living, in Ernest Becker’s sense, in fear of death: incessant and often ridiculous attempts to preserve eternal youth, the endless planning of new cosmetic procedures, a frantic clinging to inevitably fading external beauty, the “recruitment” of younger partners by aging sugar daddies, and so on. This is a hovering in a parallel reality, far removed from real life — also in Lacan’s sense of the Real — where clarity about what gives life meaning is absent. In practice, such a state is anxiety-inducing and ultimately unbearable.

The antidote to “flying off into the clouds” is not “living in the moment,” enjoying whatever life remains, or “filling one’s own cup” so that one can finally “start living for oneself.” The antidote lies in the understanding that every hour acquires weight only when it is lived in a way that allows one to realize one’s potential in the deepest and heaviest possible sense—for oneself and for one’s children.

This is precisely what “tying up loose ends” means. For men, this process should begin no later than at the threshold of the fiftieth year. And if it lasts a long time, then let it last — the better for it. At least then that time is not spent increasing tragedy in the lives of others through one’s unintegrated inner darkness, but rather in doing something from which something good might emerge.

Tying up loose ends

The “tying up of loose ends” that becomes unavoidable, in terms of meaning, from around the age of fifty may seem like a deeply depressing thought — much like the realization that life is, in its basic nature, suffering. Yet paradoxically, this realization points in exactly the opposite direction. A person can move through distinct phases: the complete ignoring of death (childhood and early youth); a willful and essentially childish flight from the thought of death (talk of how, at fifty, half of life still lies ahead and everything is possible); and finally, taking responsibility for one’s actual age and calmly beginning to tie up loose ends.

Tying up loose ends primarily means two things. First, it very plainly means stopping childish foolishness. The Apostle Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 13:11 (KJV): “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” Fifty could be the final boundary at which a man stops talking nonsense and stops consciously misleading himself and others with stories he no longer believes (or perhaps never truly believed at all). Instead of engaging in actions that, in the larger scheme, do nothing but increase suffering in his own life and in the lives of others — above all, in the lives of his children — he could simply stop.

There is little worse than a man in his fifties who remains a “teenager,” chasing short-term pleasures and thereby creating for his children a distorted and pathologically deviant image of intimate relationships and family life. This happens, for example, when he attempts to present his lover a quarter-century younger — who is willing to have sex with him in exchange for travel and a car lease — as some kind of “mother-like figure,” even though by age she is closer to an older sister or girlfriend. If the child simultaneously has, for instance, a biological mother as a model and lived example of a meaningful relationship grounded in marriage and family, then such a father knowingly damages his child — driving cognitive dissonance into the child’s inner world and sacrificing the child’s future to his own orgasms. The “aging playboy” in his fifties is little better, nor are various forms of polygamous arrangements or “open marriages.” No matter how one attempts to justify them, they still constitute a deviation that veers toward pathology. At some point, one might abandon childish antics.

Unfortunately, this is not fundamentally different from women in their thirties and forties — often single mothers — who cling to the myth of eternal youth and intoxicate themselves with male attention from men as a substitute for life’s deeper meaningfulness through family. In more tragic cases, they become stepmothers to their own children, scarcely different from the “mother” in the fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, who left the children in the forest and said: “Do not be afraid, children. Stay here and sleep peacefully. We are going into the forest to chop wood and will come back later and take you home.” The contemporary version of this is leaving for a lover with the promise: “Don’t be afraid, children. Stay here and sleep peacefully. Mommy is going to get ice cream and will come back home.” In reality, the mother goes to her lover or sugar daddy; the children wait, become disappointed, and get lost — exactly as the narrative logic of the fairy tale predicts. In an even more pathological scenario, a mother who has become a stepmother to her own children systematically dismantles the ideal of family and the children’s understanding of a meaningful life by attempting to integrate a constantly changing series of partners, or sponsor-like sugar daddies, into the children’s lives as “father-like figures.” In practically all cases this ends tragically: it offers only a brief escape from reality and, while trying to present a cheerful image of “family,” in fact delivers a warning to the children — showing the mother as hedonistic and unstable, or in the worst case as someone in a transactional relationship - a prostitute with a single client. Here, incidentally, the absence of the father’s masculine role — the woodcutter father from Hansel and Gretel,— also comes into play: his submission to his wife’s (the Hansel and Gretelstepmother’s) wish to “get rid of the children.”

Thus, if the first part of tying up loose ends is clearly stopping idiotic behavior, the second part is creating practical guidance for life for one’s children (and others). Naturally, the first is a prerequisite for the second, and the second, in turn, necessarily involves the father’s active engagement.

These guidelines do not arise from “writing manuals,” nor from quoting Eastern philosophers or Hegel in places where one does not fully understand them. That would be mere posturing and, in the end, a cautionary farce. Teaching children survival skills happens through writing the manual with one’s actions — daily, through the “golden gray everyday life,” through moral absolutes that are difficult to follow but whose violation should be even more frightening.

It means speaking to children about life and showing it to them directly, acknowledging the pain of collisions with reality and being present for their recovery from those blows. It stands in contrast both to the passive, beta-father of Hansel and Gretel and to the self-centered, hedonistic mother (who, as far as I know — I hope I remember correctly, but in terms of narrative logic it is in any case fitting — dies before the end of the story), or worse still, the witch who builds an addictive gingerbread “cloud city” for the children, fattens them up, and ultimately eats them.

Of course, these archetypal vices exist in all of us, and behaving this way is always easier. Yet it is precisely in this manner — by choosing what is easy over what is right—that we become pseudo-parents, stepmothers to our own children, or sugar daddies who justify their hedonistic lifestyles and lack of a substantive value system right up to death, from which they feverishly flee.

The alternative is to write those guidelines through one’s actions, doing so for one’s children and together with them: remaining honest, allowing honesty and truth to wound them when necessary, and being present in just the right measure so that they nevertheless survive and come to understand the nature of care.

Only then — by doing this, day after day — can one write a little about it. I myself still have a great deal left undone, which is why I cannot write at length. That is tying up loose ends.

The practical dimension of tying up loose ends

After describing “tying up loose ends at fifty” and its two components (stopping foolish behavior and shaping behavioral guidelines), two things usually happen: people pause to reflect, and they want to understand more precisely how this is done in practice. This has been the case with many clients — most often between the ages of forty and sixty.

It is important to understand that “tying up loose ends” does not mean, in some morbid sense, reserving a burial plot or drawing up a funeral checklist. On the contrary — as I have mentioned before, though evidently not clearly enough — it means a shift in mindset, one in which a person acknowledges and feels the weight of time. Most plainly and concretely — and I value people who are themselves concrete and demand the same of others — this means gradually replacing oneself as a physical individual with oneself as a principle. To avoid confusion, let me explain.

A person will disappear from the world, but as an ongoing process, “tying up loose ends” allows them to bind themselves into a principle — something that points toward an ideal in all those situations where they themselves would otherwise be physically present. This is not merely about creating memories with children by buying them unnecessary things, nor about striking poses while “playing” at being a parent. Rather, it involves a deep understanding of a child’s prospective life trajectory and the shaping — and sufficient “rehearsal” — of principles that will later enable the child to decide reflectively how to act.

For example: if the child grows up to be a woman, she will automatically reject transactional relationships, clearly seeing what follows from selling one’s body for small change to sugar-daddy-type sponsors. She will be able to resist short-term temptations (variety, exotic travel, gifts) in favor of enduring values (family, home, marriage), thereby excluding — at least for herself — the possibility of becoming a stepmother to her own children.

If a boy grows into a man, this is expressed above all in the assumption of responsibility through absolutes and boundaries: avoiding patterns of behavior in which lying, reneging on agreements, and eventually even comical self-justification lead one to become an old man abandoned by his children, fleeing responsibility and growing cynical toward love, family, and marriage — instead of being, to the best of one’s abilities, a dignified father.

The same logic repeats itself in a corporate context. It is an approach through which a leader gradually makes himself “unnecessary” — and even the quotation marks feel inappropriate here. More accurately, he replaces himself with a principle that is so clear that his personal presence is no longer substantively required.

On a daily level, this also means greater decisiveness and a direct confrontation with one’s fears in the most literal sense. Observing people who have mentally reached the phase of “tying up loose ends,” one can speak of three-layered thinking.

Such people acquire the ability, in every situation, to see themselves and their thinking from the outside on three levels: mathematical, psychological, and axiological (value-based). This represents a holistic transformation in the experience of being in the world. Mathematical thinking (not merely arithmetic realism, but a mode of thought) corresponds to ontological reality; psychological thinking (understanding one’s feelings, reactions, pain, potential wrongdoing, and gratitude) corresponds to the epistemological level of perceiving reality; and seeing life through value hierarchies corresponds to the axiological component. What happens in practice when such a mode of thinking is applied? A person uses their time well — acts purposefully and — and this is a slightly strange yet very positive side effect — decides quickly and breaks rules in the best sense, when they know what they are doing.

Thinking, seeing the world, and living with the aim of gradually replacing one’s physical existence with oneself as a principle naturally involves assuming enormous responsibility — often far more than one can comfortably carry — but it also changes how one behaves. Many have said that after such a “tying up of loose ends at fifty” (whether before or after reaching that exact age), a person also becomes “simple” for others. Perhaps that is not such a bad thing.

And now I will really stop. That is tying up loose ends.