The limits of Western spirituality – when the “bliss” starts to fade

When analyzing human behavior and motivation in a corporate context, we increasingly encounter spirituality in its various forms. It was precisely this recurring exposure that, within the framework of the Self Fusion project, led to the development of several assessment and analytical methods designed to examine the effects of spirituality - especially in organizational environments - in a sober, structured, and rational manner. This article is grounded in that pragmatic analysis and identifies three central limitations of spirituality that are rarely addressed directly. Yet these limitations constitute the substantive reasons why the majority of contemporary spiritual approaches are not only difficult to implement within organizational frameworks, but in certain cases also lead to distinctly negative outcomes.

Playing with levels of consciousness

When one soberly examines how people most often become captivated by spirituality, it is possible to distinguish two psychological processes that operate in parallel.

First, individuals are presented with thought experiments concerning consciousness in a domain where no exhaustive scientific or strictly rational explanation exists - especially at the level of self-consciousness. This frequently produces a sense of awe-inducing ignorance, which has a psychologically deep and destabilizing effect.

Second, an apparent explanation is offered to fill this ignorance - most often framed in terms of different “levels of consciousness” and “energies” - which the individual begins to believe, often with the conviction that they have attained a final understanding of life, consciousness, the universe, love, freedom, and even their own “true nature.”

The presentation of consciousness as a multi-layered structure —

the empirical subject as an identity acting in the world,

a reflective consciousness capable of thinking of itself as a subject in the world,

and a more general, prior, and enabling conscious structure —

is not, in itself, anything new. Versions of this idea already appear in ancient philosophy and later in the work of René Descartes. It is analyzed with particular rigor by Immanuel Kant, where the final layer emerges as the transcendental unity of apperception. Variations of the same problem are further developed by Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and, in a different register, also by Martin Heidegger.

The problem, therefore, does not lie in recognizing the multi-layered structure of consciousness as such, but in the way this unavoidable limitation of human reason is monetized within various forms of spirituality. Where Kant explicitly acknowledges the inability of human reason to fully conceptualize things in themselves and draws strict boundaries around what can be asserted by reason, many practitioners of Western mystical spirituality step in and actively offer seemingly persuasive and psychologically compelling interpretations of precisely that which cannot be conceptually grasped.

The problem is compounded by the fact that these interpretations appear convincing precisely because there is no meaningful way to verify them, to oppose them through argument, or even to formulate them rigorously at the level of a hypothesis. Such approaches are presented as “experiential” - valid and fully accessible only if one happens to reside at the “correct” level of consciousness.

To be sure, the mere fact of consciousness can be analyzed, for example, in informational terms- as in Integrated Information Theory, where consciousness is described as an integrated difference between input and output. Yet we still know nothing about the nature of consciousness that would allow us to derive from it metaphysically binding or normatively obligatory conclusions.

It is precisely here that we encounter the fundamental problem due to which many theories and practices that apply this approach consistently collapse in the end - both in corporate and private life. That problem is the absence of moral responsibility, which proves to be the most fundamental weakness of such systems.

Closely connected to this are two additional, parallel problems: the avoidance of unpleasant but necessary actions, and the systematic overestimation of one’s own abilities and achievement potential. I will address all of these next.

The fundamental problem of moral responsibility

It is painful to observe how several otherwise serious psychoanalysts have drifted into the gravitational pull of a pantheistic worldview and, as a result, begun to operate in an internally divided manner. On the one hand, they understand, value, and apply dynamic approaches in psychotherapy that presuppose responsibility, causality, and inner conflict. On the other hand, they simultaneously describe the universe in pantheistic terms, where individual agency and moral responsibility dissolve into an impersonal whole.

Such frameworks inevitably generate an internal contradiction that can be avoided only as long as neither line of thought is carried through to its logical conclusion. Once one attempts to do so, the contradictions prove structurally irresolvable.

When Immanuel Kant wrote Critique of Pure Reason, he arrived at an epistemological paradox that, at least at first glance, placed his entire moral-philosophical project under serious tension. Kant demonstrated that the world as we experience it is always already structured by our cognitive faculties: we never encounter “things in themselves,” but only appearances (phenomena), shaped by space, time, and the categories of understanding. In this sense, the world is never immediately objective reality for us, but always experientially mediated. This does not imply that an objective world does not exist, but rather that we can never know it outside our cognitive structures. When this line of reasoning is worked through rigorously - together with the contributions of David Hume, Schopenhauer, Fichte, Schelling and the legacy of ancient philosophy - this epistemic boundary becomes both clear and logically unavoidable.

Yet it is precisely here that a rarely articulated but fundamental problem emerges. If each person experiences the world solely through their own cognitive structures, what is the ontological and moral status of other people within that world? Others cannot be mere “constructs” authored by my consciousness, since they present themselves as equally perceiving, evaluating, and independently acting subjects in their own right.

It is for this reason that Kant was compelled to formulate his moral philosophy in the form of the categorical imperative and to supplement epistemology with a normative moral (axiological) structure. One must act only according to maxims that could become universal laws. But this immediately raises the decisive question: before whom does this responsibility hold? Whom do we owe the fidelity to? Who is the instance that judges whether the “law” has been followed? I have addressed this question in greater detail in my fourth lecture on Kant, The “Third Self” and the Problem of Intersubjectivity.

If one restricts oneself solely to the epistemic conceptualization of consciousness and world, responsibility ultimately collapses into responsibility only before oneself. Moral obligation is reduced to an internal self-rule rather than a norm possessing person-independent and universal validity. It was precisely this epistemological limit that forced Kant to distinguish practical moral reason from pure theoretical reason and to articulate moral responsibility as an autonomous normative structure - one that does not negate human “authorship” of experience, but nevertheless imposes a binding moral framework upon it.

Here we arrive at the decisive fork from which many subsequent problems unfold, and which defines the deep tension between religious dogmatism and fluid Western spirituality. This is the problem with which Friedrich Nietzsche struggled intensely throughout his life, arriving at an exceptionally precise diagnosis, but not at an exhaustive solution.

Western spirituality often moves decisively in one direction at this junction: away from categorical norms and moral absolutes, while simultaneously employing rhetorical terms such as “truth,” “authenticity,” and “responsibility.” When consciousness is conceptualized at its most general level - as an impersonal field in which both “you” and “I” dissolve - responsibility inevitably contracts into responsibility only before oneself as the author of that field.

If you and I are, in the final analysis, one and the same; if this unity is simultaneously creator, universe, god, love, freedom, and consciousness, then everyone is responsible for everyone- and no one is responsible before anyone. The moral judge and the bearer of responsibility collapse into a single position. I decide what is right and what is wrong.

It is precisely here that the problems emerge which explain why even highly intelligent and rational thinkers - such as Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, and Daniel Dennett - have ultimately failed, at least in part, in their projects, becoming entangled in the unresolved question of the source of moral normativity. The cultivators of Western spiritual mysticism, however, rarely allow themselves to be disturbed by this contradiction.

Spirituality’s solution: the pursuit of happy states

If we extend the logic of responsibility that ultimately limits itself to responsibility only before oneself, it becomes clear that this form of Western spirituality offers extraordinarily seductive “moral tools and levers.” The most correct choice at any given momentv - both in individual decisions and in life as a whole - is that which makes the individual subjectively happiest: the action, the mode of being-in-the-world that maximizes lightness, well-being, and happiness; that provides the experience of loving (and, often though somewhat less centrally, the feeling of being loved); and above all, an all-encompassing sense of intense freedom.

All other forms of action that diminish this sense of happiness are, within such a spiritual ideology, associated with the “pathologies” of lower levels of consciousness - desire, anger, sadness, pride, or fear, or, in the worst case, their apparent absence in the form of withdrawal into lethargic apathy. Toward those perceived as residing on these “lower levels,” one is encouraged to display compassionate understanding, yet descending to such levels oneself is treated as an unmistakable regression. In this way, by systematically maximizing subjective happiness, a person can select a mode of being-in-the-world in which one is “constantly well and blissful,” and the entire perception of reality is transformed.

The experience of being alive is transfigured into a state of blissful lightness, comparable to the way The Unbearable Lightness of Being (by Milan Kundera) portrays (in its final phase) Thomas’s existence - pure love, weightlessness, and a form of being unbound by ties or obligations. It is precisely here, however, that the first serious collision with reality occurs - although many spiritual frameworks themselves do not acknowledge “reality” as such. Reducing moral responsibility to responsibility solely before oneself, and systematically avoiding moral absolutes, effectively leads to the emergence of a distorted religion of pleasure. While most practitioners do not explicitly acknowledge this, what is at stake is moral relativism in its purest form.

As noted, the individual simultaneously occupies the role of moral judge and moral subject. When the guiding question becomes which choice is “right” and which allows me to exist in the freest and happiest possible state, people generally do not choose the most unpleasant, demanding, or psychologically and physically sacrificial actions.

From a psychoanalytic perspective - which, incidentally, many such spiritual practices tend to dismiss rather lightly - this creates a particularly problematic situation. The individual evaluates which option feels most correct in terms of immediate subjective happiness and acts accordingly. In effect, conscious reasoning becomes “armed” with a mechanism that allows nearly any unconscious impulse to be rationalized and subsequently labeled as the morally “right” choice.

Within such a framework, it becomes exceedingly difficult to maintain that lying is always, in principle, wrong, or that betrayal and the violation of agreements are unconditionally morally reprehensible. The very possibility of moral absolutes collapses precisely because the concept of truth itself is treated in an extremely tendentious manner.

At this point, a central spiritual “sleight of hand” takes place. Truth and honesty are rhetorically emphasized as core values of the lived experience. Yet the conception of truth is then taken one step further - beyond even the position articulated by Martin Heidegger in The Essence of Truth. Truth is equated with Being itself, and honesty ultimately reduces to honesty toward oneself. A person is free and “enlightened” insofar as they remain sincere primarily toward themselves in every situation.

Such an approach effectively nullifies the principle of opposing unconscious drives and, in the final analysis, dissolves the unconscious itself as a problematic structure. The issue is no longer the regulation or integration of impulses, but merely the “degree of enlightenment.” One should not do anything that does not produce happiness; the unpleasant and the painful are to be avoided, because the aim of life becomes the continuous occupation of varied, subjectively pleasant states.

The corporately logical outcome: lower pay or unemployment

Comprehensive analyses of employees’ “career life cycles” point to a phenomenon that is so obvious in its structure that articulating it can feel almost inappropriate. An individual who systematically avoids unpleasant, effort-demanding, or short-term non-rewarding activities, and instead focuses primarily on subjectively nourishing and happiness-producing actions, will in the long run typically earn significantly less money. Paradoxically, such individuals also tend to reach burnout - or pre-burnout states - more quickly.

Let us examine this logic in strictly pragmatic terms. The combination of maximizing one’s subjective happiness, working in a “constant bliss state,” and simultaneously maintaining and increasing competitiveness would be theoretically possible only if all other market participants operated according to the same life philosophy. In such a scenario, a continuous “win–win” logic, mutual support, and general harmony could indeed prevail. In practice, however, this rarely occurs in corporate environments - often not even within a single organization, let alone across the broader market.

Empirically, it is evident that those most psychologically receptive to the pursuit of constant subjective well-being tend to share a particular personality configuration: high agreeableness and compassion, elevated empathy and social politeness, higher neuroticism (especially in the direction of withdrawal), lower aggressive assertiveness, and average or lower industriousness. This combination - more common among women - is not morally problematic in itself, but becomes destructive in terms of career development in environments where competition, hierarchy, and performance are unavoidable.

Such a personality profile would function exceptionally well in an ideal world in which everyone else followed the same logic. In real organizational settings, however, these individuals frequently find themselves working alongside colleagues whose profiles are nearly the inverse: high industriousness, strong assertiveness, lower empathy, low biological politeness, a high tolerance for unpleasant and demanding tasks, and continuous skill development (openness to ideas).

Under the influence of a spiritually happiness-centered worldview, such ambitious colleagues are rarely interpreted as professionally admirable or as role models worth learning from. Instead, they are often perceived as operating on “lower levels of consciousness”- driven by desire, pride, or aggression - toward whom compassion and understanding should be shown, but whom one should neither follow nor emulate. And yet, it is precisely individuals with these traits who earn higher salaries, advance more rapidly into higher positions, and achieve material independence significantly earlier.

This logic - however uncomfortable or “unspiritual” it may appear - is built directly into the operating mechanisms of capitalist economic systems. What, then, typically happens to those who are “highly evolved” in spiritual terms but whose professional results remain modest? Most often, this does not lead to the assumption of total personal responsibility. Because the work environment does not increase subjective happiness, dissatisfaction is reinterpreted as an external problem. The cause is not identified as one’s own reduced willingness to engage in unpleasant, effortful, or short-term unrewarding tasks, but rather as the employer’s failure to create a motivating, balanced, supportive, and “energetically correct” work environment.

Within this logic, burnout begins to function as a paradoxical ideal - a symbol that primarily signals the failure of the organization or employer, rather than the individual’s own unrealized potential. Responsibility in the “enlightened” mind shifts from the individual to the system, from which one must exit instead of changing oneself.

The absence of morality as an obstacle to personal development

At first glance, one might assume that aggressive competition and confrontation - especially when interpreted through the language of “levels of consciousness” - are merely expressions of power hunger or financial greed on the part of people operating at a “lower level,” and that such individuals simply perceive life and the world incorrectly or incompletely. In certain situations, there may be a partial truth in this view. However, such an emphasis addresses the problem only superficially.

What differentiates people in terms of career development, growth in quality of life, and the achievement of long-term balance is not how much money they desire or are willing to accept, but rather a highly pragmatic combination of industriousness, intelligence, assertiveness, and - as corporate analyses increasingly confirm - moral structure.

It is precisely the presence of moral absolutes and adherence to them, together with an awareness of one’s personal limitations, that provides individuals with significantly stronger preconditions for success - both in capitalist society as a whole and in professional life in particular (especially in leadership roles). This also offers a relatively straightforward explanation for the recurring patterns observed in analyses: successful individuals are often highly industrious, intelligent, relatively assertive, frequently extraverted - and at the same time morally structured.

This typically begins with accurate self-perception. In contrast to spiritual logic, where individuals tend to believe they are “essentially good,” focus on maximizing subjective happiness, and regard themselves as capable of anything while being accountable only to themselves, corporately successful individuals exhibit a markedly different psychometric profile and value framework.

They do not consider themselves intrinsically “purely good.” They acknowledge both good and bad within themselves - often even a considerable amount of the latter, manifesting as problematic impulses. They consistently focus on unpleasant, effort-intensive, and short-term non-rewarding activities. They understand that maintaining competitiveness requires continuous learning and skill development. And the higher they rise within organizational hierarchies, the more they come to value moral absolutes and a clear normative structure that stands above them, rather than relying solely on an internal, subjective sense of “right” and “wrong.”

They also understand that personality traits are largely innate. Most psychometric traits can be altered only within narrow limits - typically by a few percentage points (with the obvious exception of IQ, which cannot be increased). The myth of a sudden vertical “quantum leap” into a new personality or level of capability therefore appears to them not as a viable strategy for long-term success, but as a dangerous form of self-deception and rationalization.

Employees captivated by spirituality, by contrast, often redirect their energy away from increasing professional effort and toward spiritual practices. As a result, they do not begin to earn more money, but instead become accustomed to lower income - despite “loving money,” manifesting it, and considering themselves open to greater material success.

From an objective standpoint, this frequently reflects lower professional potential, insufficient skills, and - at the personal level - excessively high agreeableness, which inhibits the willingness to take unpleasant but developmentally necessary steps. Rather than realizing the potential available to them within the constraints of their actual personality traits and thereby improving their quality of life, such individuals replace realistic self-assessment with a belief in unlimited personal capacity - ultimately distancing themselves from rational thinking and responsibility altogether.

Value systems have a maximum load-bearing capacity

The more significant the situations of conflict and confrontation in a person’s life are (and their occurrence is built into the very structure of life itself), the more difficult it becomes to deal with them without moral absolutes - while remaining morally flexible and fully committed to a “win–win” mentality. It is precisely here that we arrive at a fundamental contradiction: is reaching the highest level of consciousness sufficient, or is a form of moral normativity independent of consciousness still required? The more existentially significant a question becomes in a person’s life, the clearer it becomes that an axiological component is indispensable in shaping one’s worldview. Purely ontological and epistemological approaches prove insufficient.

There are highly intelligent individuals who have reflected deeply on their lives and nevertheless deny that they follow any value system at all. In most cases, however, an ideal still exists in the form of a hero - ranging from fictional characters (such as Batman) to religious, ideological, or spiritual exemplars. Although this claim may sound radical—and based on my own reading, I do consider it genuinely radical—I maintain that the load-bearing capacity of value systems is quantifiable, analogously to engineering: as in the load analysis of a bridge, a dam, a building, or even a software system.

People whose value systems are more fluid, elastic, and minimally constrained often experience everyday life as easier and less internally tense, frequently without any awareness of the lower load-bearing capacity of their value systems. When an existential crisis arises - the death of a loved one or a child, the collapse of a long-term marriage, a total socio-economic breakdown, and so forth - the true load-bearing capacity of a value system is inevitably put to the test.

If a person has lived in a way that is daily more demanding, deliberately exercising free will in order to submit to a restrictive and normative value system, their ability to cope and to maintain emotional stability in such circumstances is far more likely than that of someone primarily focused on maximizing subjective states of happiness. This is supported by multiple empirical studies, particularly in the context of the most tragic life events or so-called “blows of fate” - to use Shakespeare’s formulation, the whips and scorns of time.

Western spiritual philosophy often assists individuals in constructing a value system with very low load-bearing capacity, grounded in moral relativism and epistemic volatility. As long as this system is not tested, everything appears to function well. When that moment arrives, however, it most often collapses. It then becomes evident that many of the internal “cores” upon which a person has relied as sources of strength, meaning, and vitality function only during periods when life is broadly stable, and lose their carrying capacity - sometimes even becoming self-destructive - precisely when one enters conflict situations in which moral absolutes stand in opposition.

To illustrate this phenomenon, consider the anatomy of infidelity. A highly spiritual man cheats on his wife in a long-term marriage. He does not do so out of revenge, nor out of desire in the classical, instinctual sense. He perceives energies and at some point arrives at the understanding that the universe has given him a secretary with whom he simply must also become physically closer. First, this is to some extent predetermined; second, it helps restore a long-awaited balance in his intimate relationship. Such a situation may continue for months or even years, until, for example, the man’s wife becomes suspicious.

At the same time - since everything is ultimately one and the same: the man himself, his wife, the secretary, consciousness as such, the experience of being alive, love, and freedom—moral judgment is reduced primarily to a matter of perspective. Introducing condemnation from a Christian religious standpoint would amount merely to opposing the multiply interpretable views of one possible “enlightened master” (who, allegedly, spent ages twelve to thirty in India anyway) to those of all other enlightened figures.

Can withholding information from one’s spouse even count as dishonesty if, in a spiritual sense, the man remains honest with himself, does not wish to harm anyone, and merely participates in the “game of life,” which is largely predetermined? From a spiritual perspective, it becomes exceedingly difficult to impose any moral frameworks or demands in such a situation, because the man, accountable only to himself, remains “pure” - and, moreover, significantly happier.

If it then turns out that the faithful, principled wife, upon learning everything, proves to be a morally very “radical” person - initiating divorce, using every available means to secure child custody, to obtain the maximum possible share of joint assets, and losing all respect for her former husband - one might be tempted to describe her as a “spiritually underdeveloped” woman: bitter, feeding her pain-body, incapable of grasping the logic of freedom and universal oneness. Yet the question is far more fundamental: is the chaos that results from spirituality colliding with moral absolutes not, in fact, an expression of life’s own logic?

If, for instance, such a woman enforces a custody arrangement that significantly reduces the cheating father’s time with his children - despite his sincere wish to be present - we can endlessly reframe the situation through a “win–win” logic and analyze it from multiple angles. Yet for most people, often including the man himself, it remains deeply unclear where exactly his “win” lies, when he cannot spend time with his children, has far less money and opportunity, and faces an entire array of new problems.

From a spiritual standpoint, the man truly did nothing explicitly wrong at any point. At every moment he acted honestly toward himself. He listened to his intuition, tracked energies, trusted the flow, and consistently maximized his personal happiness and experience of lightness. He distinguished right from wrong, good from evil, exactly as Western mystical, consciousness-based spirituality prescribes: not through external norms, but through internal resonance. He did not betray his truth. He did not go against his feelings. He did not force himself into situations that felt inauthentic, difficult, or “low-energy.” At every moment, he chose what felt most liberating, most authentic, and most aligned with his inner experience. He lived by the teachings exactly as they are commonly articulated: be honest with yourself, choose love, avoid constraints, do not force yourself into frameworks that do not serve your growth. And precisely for this reason, it is impossible to point to a single moment in which he erred in a spiritual sense.

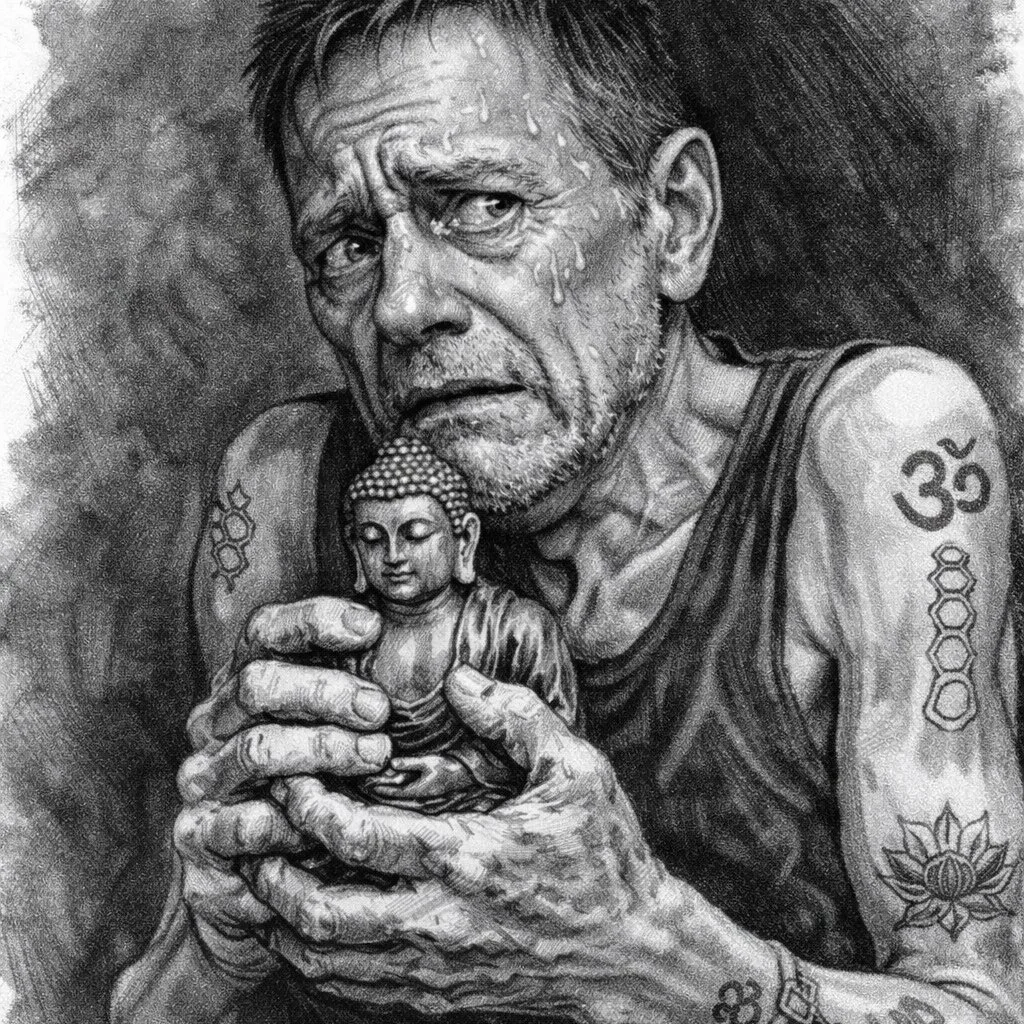

And yet, now he has no family, no secretary (who moved on to the next sugar daddy), no home, no clear vision of the future, and no material security. His self-respect fluctuates. Relationships have collapsed or emptied out. And as one person put it with striking honesty: “the bliss somehow starts to fade.”

So what went wrong? This question exposes the core contradiction: if all decisions were made according to the logic of momentary inner truth, freedom, and happiness maximization - if the individual was honest with himself at every step and on the “correct level of consciousness”—then no clear error can be identified. And yet the outcome is what it is. This means the problem did not lie in individual choices, but in the framework itself. If a system allows one to act “correctly” at every moment and still arrive at existential collapse, the issue is not error, but the absence of moral structure.

One could, of course, still claim that everything went exactly as it should have - that life foresaw it all, that this was a “liberating restart into freedom” and into even higher levels of consciousness. At the same time, the children are disappointed in their father, they do not understand the logic of “everything is one,” and many “overly morally constrained and spiritually retarded” people judge him harshly. Several even refuse to cooperate with him, because a relationship with a secretary twenty or thirty years his junior appears to them - given their limited level of consciousness - transactional and hedonistic.

This is not a fictional example. There are many such stories. Very often, this path also leads to professional burnout. As many individuals who later came to view this form of spirituality more soberly have retrospectively acknowledged: there is nothing good in the chaos produced by the systematic pursuit of blissful states and a life without moral structure. This is not some profound “learning experience,” developmental phase, or liberating “opportunity.” It is a massive, exhausting, and deeply demoralizing mess.

There are many situations in life where “win–win” simply does not exist, and morality-free spirituality leads only to deepening chaos. An ideal illustration of this is the divorce of two deeply spiritual people. If one assumes that such processes are inherently blissful, humanistic, and mutually benevolent, this is simply an inadequate description. Exactly what was described above comes to pass. The decisive advantage goes - often while seriously harming (or completely destroying) the other person - to the party that adopts moral boundaries and uses them strategically. And when neither party possesses moral absolutes, the one who prevails is the individual whose psychometric profile includes higher aggression and assertiveness, and lower agreeableness, compassion, biological politeness, and neuroticism.

Spirituality, and any ontological or epistemological constructions lacking a moral vertical, are ultimately not viable. They may offer temporary justification, inner calm, and subjective meaning, but they do not carry a person through life situations in which decisions have irreversible consequences for others. These stories are already written. And until we learn from them, one may soothe oneself spiritually in any manner one wishes - but perhaps this is not always the card on which one should stake one’s life.