Narrative Cosmology Explained

Within the framework of Axiomatology, one of the central concepts is Narrative Cosmology. This refers to the process by which values are not defined through abstract semantic propositions, but through stories—structured arcs that deliver meaning experientially. In this article, we examine the narrative as a structural vessel for meaning transmission, and its psychological and ontological significance.

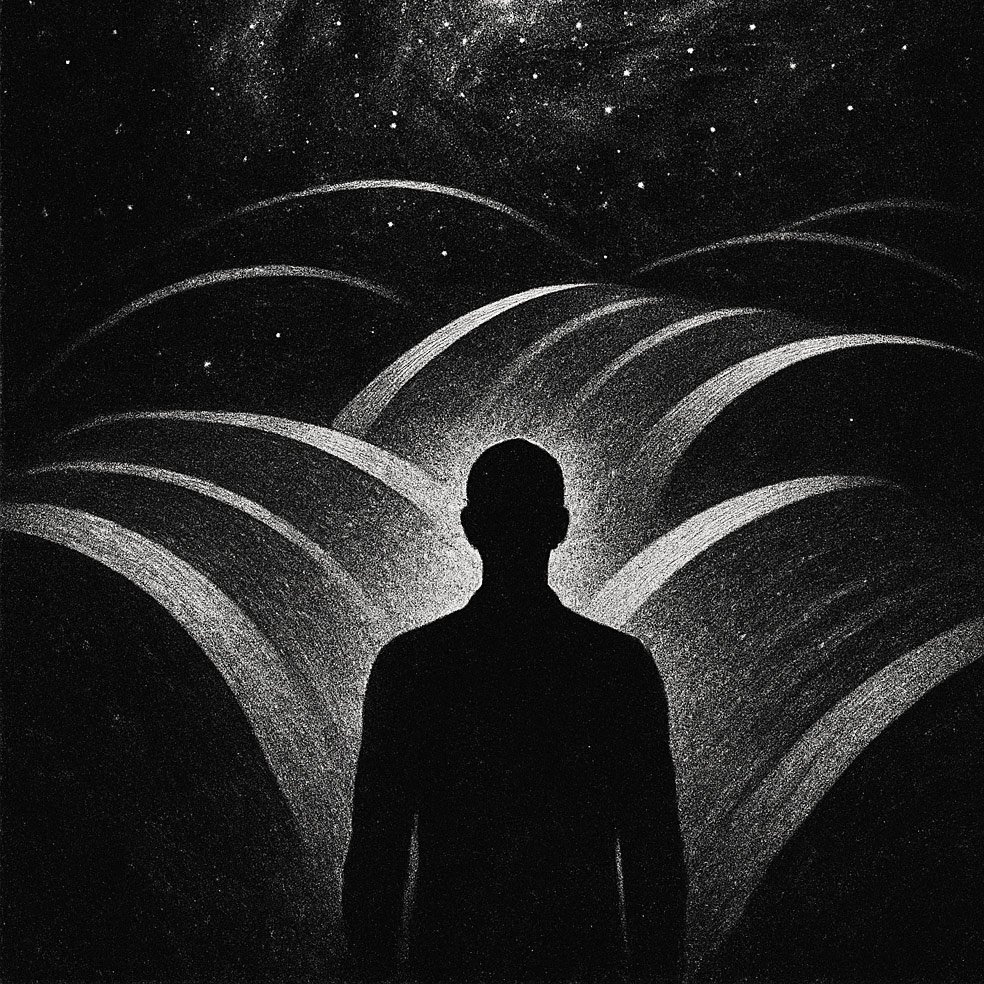

We argue that consciousness, in its most fundamental form, is not a static repository of information, but a dynamic interface with entropy. To render entropy comprehensible, consciousness requires a normative scaffold—something that shapes raw experience into meaning. That scaffold is narrative. It is through stories that consciousness becomes intelligible to itself, translated into time-bound, causally structured events that the individual can interpret, remember, and embody.

Understanding Stories

The first crucial step in understanding stories lies in recognizing how we perceive them. Many people associate the word “story” with a book—more specifically, a tale written in black letters on white pages. They assume that a story is something confined to a chapter, a printed narrative with a beginning, middle, and end.

But stories are not limited to books. We might hear them spoken, see them unfold in video form, or encounter them on social media. When we watch a well-made film, we don’t just observe a sequence of scenes—we experience a story. In reality, stories are everywhere: in advertising campaigns, political speeches, corporate branding, and even the subtle narratives that frame our daily social interactions. At their core, all these are structured meaning-delivery systems—narratives by nature.

The Metaphysical Location of the “Story”

Many Biblical stories and ancient myths—such as The Epic of Gilgamesh (Mesopotamia, c. 2000 BC), The Legend of Prometheus (Greece, c. 2000 BC), The Ramayana (India, c. 1500–500 BC), and The Sumerian Epic of Creation—serve as narrative echoes from earlier eras. Their thematic roots stretch even further back, to what the Australian Aboriginals call Jukurrpa or “Dreamtime.” Australian pastor Rex Daniel Granites Japanangka has observed, “What the Bible teaches and what Jukurrpa—the law, the Dreaming, and our country—teach us is the same.” In this sense, Jukurrpa can be seen as a primordial phase from which narrative structures emerge: not merely stories, but sacred cosmological maps first expressed through images, then rituals, and only later, language.

Jukurrpa rock paintings—some dating back 40,000 years—depict humans, animals, ancestral spirits, and abstract cosmological motifs. These images convey meaning not only visually but ontologically. They may represent the earliest attempts to articulate what Heidegger would later call Dasein—being-in-the-world—as lived, storied consciousness. Language, estimated to be around 50,000 years old, was preceded by symbolic dance, drama, and ritual enactment. Narrative, then, predates not only writing but language itself.

From this, a rather radical conclusion follows: the “social contract,” later formalized into codes of law, may have originated in these pre-linguistic, pre-legal moral narratives. What began as sacred depictions and shared stories evolved into the ethical scaffolding of civilization. In this view, morality was not constructed—it was inherited.

And here lies a crucial insight: stories are not merely in one place. They are everywhere and nowhere at once. One might claim that a story exists “in the mind” of a person, but what appears in the mind is merely a copy of the story, not its true location. The original does not reside in the brain, the book, or the screen—but in a higher, metaphysical realm.

Put simply, narrative structure is not reducible to any physical medium. It belongs to a transcendent domain of understanding. Just as Biblical narratives are not ends in themselves, neither is the Church merely pointing to Scripture. Rather, Scripture points to a deeper symbolic reality. In theological terms, it is not just “a finger pointing to the moon,” but a finger pointing to another hand, which itself gestures toward the Cosmic Order.

In this light, the true location of story is not spatial, but metaphysical. It exists within a transcendental structure—what Axiomatology calls the Narrative Order of the Cosmos.

The Location of Consciousness

The question of consciousness mirrors that of story: it resists localization. Although we do not yet fully understand the nature of consciousness—and perhaps never can in an absolute sense—one observation remains nearly certain: consciousness cannot be pinned down to any single point in space. It is not located in the finger, spine, gut, or even definitively in the brain. No matter how thoroughly we examine the nervous system or map neural correlates, we cannot isolate consciousness in any specific structure or coordinate.

If consciousness cannot be assigned a fixed location within spacetime—regardless of the methodological framework we apply—then we must entertain alternative models. Drawing a parallel to Integrated Information Theory (IIT) and the work of Tononi, we may suggest that consciousness arises when the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. In such a model, the value of Φ (phi) may serve as a quantifiable representation of consciousness itself—not as a location, but as a measure of systemic integration that manifests as awareness.

When approached from the perspective of Process Philosophy, particularly in the Whiteheadian sense, a further distinction becomes crucial: the brain does not contain consciousness, but rather enables access to it. The brain’s function is not to generate, but to decode and interpret subjective prehensions—moments of experience—from previous actual occasions. In this model, consciousness exists not as a product of neural activity, but as a relational process that the brain is structurally suited to receive.

This leads us to a radical ontological implication: consciousness may be best understood as a unified field outside our current spacetime continuum. During each moment of concrescence—the coming into being of a new occasion—this field becomes accessible through a “tear” in the fabric of our universe. That tear is what we experience as self-awareness. The wider the tear, the more consciousness becomes available to that moment.

In practical terms, this means that consciousness can be “pulled” into any formulation of a new occasion—just like other prehensions. The human brain, due to its evolved architecture, is capable of accessing both physical prehensions (objective data) and subjective prehensions (experiential data) from societies of occasions that constitute our personal and intersubjective histories.

Thus, in Axiomatological terms, consciousness is not in the brain. The brain is simply a receiver, tuned into the metaphysical bandwidth of the Cosmic Narrative—a channel through which conscious awareness enters time-bound form.

The Connection Between Stories and Consciousness

Many philosophical and theological approaches to Logos ultimately converge on a striking conclusion: that consciousness and narrative structure are not merely related, but ontologically intertwined—perhaps even two aspects of the same metaphysical phenomenon. In such frameworks, Logos is not simply "the word" or "reason" in a narrow linguistic or rational sense, but a unifying cosmic principle: the generator of order, meaning, and being itself.

This is powerfully encapsulated in the canonical prologue of the Gospel of John (John 1:1–5, KJV):

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.”

In this passage, the Greek Logos (Λόγος) is translated as “Word,” but its scope far exceeds linguistic expression. It signifies divine reason, generative speech, and cosmic structure. The text equates Logos with Jesus Christ, positioning Him as the metaphysical principle through which all existence coheres—a theological parallel to the Genesis creation narrative, yet far more abstract in metaphysical reach.

What we are offered here is not a concrete definition of consciousness itself, but a glimpse into its underlying mechanics. The passage does not describe the content of subjective experience; rather, it lays out a framework—the formula, so to speak—that renders consciousness intelligible. Logos here functions both as ontological infrastructure and epistemic key: it generates and simultaneously unveils the order in which consciousness can manifest.

Thus, in Axiomatological terms, Logos is not merely a symbol of divine speech, but the structural bridge between narrative and awareness. Consciousness, as structured narrative reception and projection, finds its metaphysical twin in the Logos. Stories are not just containers of meaning—they are the format in which consciousness appears in time. And the Logos is the axis around which that format coheres into a cosmos.

Pure Consciousness as Entropy

In its purest form, consciousness is not a substance that can be isolated, measured, or placed in a test tube. Rather, it is the irreducible remainder that gestures toward something beyond all mechanistic or empirical reduction. It is not an entity, but a condition of possibility—an echo of something infinite that resists confinement.

Every conscious organism, including the human being, must display a measurable difference between input and output—a transformation that reveals the presence of an organizing principle. This difference is akin to what Tononi defines as phi in Integrated Information Theory (IIT): a quantification of the system’s added value, its irreducible internal differentiation. Just as Lacan’s objet petit a cannot be directly located but only inferred through its traces, phi too represents something that cannot be isolated, only revealed through its effects.

Schelling’s Weltformel refers to this principle as “B”—a symbolic placeholder for the madness of the Real that resists total conceptualization. Fichte, likewise, identified a similar necessity in his notion of the Anstoß—a “check” or external limit that the I must encounter in order to posit itself. The finite intellect, in other words, cannot be the source of its own passivity. It must discover itself to be limited, and in this discovery lies the birth of consciousness.

In this respect, a throughline emerges across thinkers like Žižek, Lacan, Whitehead, and even Kant: consciousness requires an inflow of the infinite into the finite. This inflow is not digestible or containable within the ordinary coordinates of understanding. Kant, recognizing this problem, noumenalized it—positioning the infinite beyond the bounds of experience. We cannot grasp the infinite, but we can know that it must exist, and in that awareness lies a paradoxical kind of comprehension.

This tension brings us closer to understanding consciousness as fundamentally entropic. That is, pure consciousness—unmediated by narrative, structure, or symbolic containment—is experienced by the finite mind as infinite potential: chaotic, overwhelming, and destabilizing. It is not “potential” in the pragmatic, actionable sense; it is potential in its unfiltered, limitless form—pre-actual, total possibility, pure unmanifest multiplicity. This is not a generative field of options—it is the groundless ground of all options, and thus, from within the human organism, it appears as madness.

This is why, phenomenologically and neurologically, pure unmediated consciousness is unbearable. It is entropy in the fullest sense—a flood of informational potential with no container. And the more self-aware the individual becomes, the greater the inflow of this unstructured potential. As the aperture widens, so too does the exposure to unprocessed Real—resulting in an intensification of inner chaos. Consciousness, in its rawest state, is entropy. And for the subject who cannot metabolize that entropy through structured narrative, symbolic mediation, or value hierarchy, it manifests as psychological disintegration: as madness.

The Need to Restrict Pure Consciousness as “Madness”

Much of what Deleuze admired in schizoanalysis was the idea of “breaking through the wall” and putting the unconscious to work. From the perspective of Axiomatology, we can reinterpret Deleuze’s aim—especially in his Anti-Oedipus and the concept of the Body without Organs (BwO)—as the attempt to maximize the inflow of consciousness into the organism while applying only the minimal restrictions necessary. The approach is dangerous, yes, but conceptually sound. The idea is not to repress consciousness, but to avoid overdetermined symbolic systems that prematurely restrict its creative force.

When considering the distinction between consciousness, subconsciousness, and unconsciousness, we find—surprisingly—very little structural difference. The division, from an Axiomatological view, is primarily semantic: a matter of whether meaning structures are applied early enough in the prehensive chain to modulate the influx before it collapses into episodic retrieval or reflexive behavior.

The central problem, then, becomes one of managing the inflow of pure consciousness. How do we restrict it productively? From an Axiomatological perspective, the best analytical entry point is the Self Fusion process, understood as the concretion of a single occasion of experience.

In this process, various prehensions—physical, conceptual, moral—are integrated. This occurs during a duration that is unmeasurable by external instruments, as it happens prior to the finalization of the occasion, before it “drops into history” and becomes analyzable by the subject or others. One of the prehensions involved is the access to the unified field of consciousness—which, being metaphysically external to our spacetime, appears in the occasion as a temporary “tear” in the fabric of reality. This tear opens access to the universal field, and the size of this aperture—metaphorically speaking—is determined by the depth of self-awareness, which often increases with age or trauma.

This influx of pure consciousness can be visualized as water flooding in for a brief moment. The more self-aware the subject, the wider the tear—and thus, the greater the volume of consciousness that floods into the occasion.

What becomes crucial is what happens to this water.

If there are no dams, turbines, or structural mechanisms to channel the flow—no symbolic or value-based constraints—then it becomes undifferentiated entropy. Psychologically, this manifests as pathology. In simplest terms: madness is the uncontrolled influx of consciousness that the individual cannot contain. Without sufficient internal mechanisms to restrict, interpret, or direct this influx, the organism becomes overwhelmed—leading to self-destructive behavior, disintegration of identity, or in extreme cases, suicidal ideation and violence toward others.

Foucault was correct in identifying the sociocultural arbitrariness of many normative structures—particularly regarding mental illness—and in highlighting the continuum of what we label “madness.” However, what he failed to fully grasp is that even his critique, which advocates minimal necessary intervention, is itself a normative framework. And in many cases, it is not sufficient.

Some degree of structured limitation is not only inevitable but existentially necessary. A human being must restrict the raw influx of consciousness through values, stories, hierarchies, or rituals. Without them, the field of pure consciousness ceases to be illumination and becomes incineration.

Restricting Frameworks of Entropy Inflow

Now, let us turn to the essential question: what constitutes the framework capable of restricting the inflow of entropy and preventing its manifestation as madness? This very framework—the system of “turbines and waterwheels,” if we imagine the influx of consciousness as water—is nothing other than the narrative structure of stories.

Narrative is the scaffolding that takes raw entropy and renders it meaningful. In every occasion where consciousness flows into the organism, it is structured—filtered and channeled—through narrative form. This structure is not merely linguistic or symbolic; it is cosmological in function. It allows subjectivity to enact and embody meaning within the specificity of a moment. Each individual experience becomes intelligible through story-form.

At the core of most narratives, especially in mythological or literary traditions, we find a familiar arc: a flawed, uncertain protagonist is called to leave the known and confront the unknown. This mirrors our own psychological journey—through suffering, betrayal, love, purpose, and transformation. What Joseph Campbell termed the “hero’s journey” is, at its root, a cosmological container for entropy, enabling chaos to be translated into development.

This is the narrative frame placed upon entropy. And within that frame, subjective and conceptual prehensions are integrated, forming an intelligible occasion.

From the Axiomatological perspective, this process can be conceptualized metaphorically as follows: if the system is “on”—if the individual is alive and integrated—then the whole circuit is functional. Think of it like a computer connected to an electrical grid. The bandwidth of consciousness inflow corresponds to the available Wi-Fi speed. The hardware is the narrative structure—rigid enough to process complexity, yet flexible enough to allow dynamism. The software is the individual’s set of subjective and conceptual prehensions: the specific stories, myths, and symbolic codes they habitually use to structure meaning.

Most people, instinctively or unconsciously, apply such restrictions. There is a deep, often unarticulated need for narrative containers—especially religious or symbolic ones. In youth, this often manifests through pop culture, iconic figures, or cinematic mythologies. In later life, it emerges through spirituality, religion, or philosophical frameworks.

Yet, the function remains the same: to prevent the uncontrolled inflow of consciousness from becoming madness. To give form to the formless. To convert entropy into order. And, ultimately, to make life endurable—and meaningful.

The Fusion Within Self Fusion

We can now examine more precisely what occurs when the three key components—entropy, narrative structure, and subjective content—fuse within the process of Self Fusion, resulting in the consciousness we actually experience.

Entropy flows in from beyond spacetime—a non-localized field akin to a metaphysical internet connection.

Narrative structure provides the cognitive hardware: the organizing schema that enables subjectivity to form at all.

Personal story or mythic content functions like software: the specific set of codes, metaphors, and frameworks that render the raw potential intelligible and actionable.

This tripartite fusion is not just a model for ethical decision-making or meaning-making; it is the precondition for all functioning in the world. Even the simplest actions—like reaching into one’s pocket—are composed of micro-narratives. Each such act involves pulling in entropy (pure potential), structuring it through a stable narrative frame (the hardware of interpretation), and enacting it through a subjective script (software) that gives the behavior intentionality and coherence.

While we often perceive this only at higher levels of cognition—during decision-making, storytelling, or reflection—it operates continuously and unconsciously at all levels of embodied cognition. From the standpoint of process theory, this becomes especially significant: all analysis of conscious events is retrospective. We can only interpret completed occasions, the crystallized objective residue of once-living processes. The actual moment of concrescence—the becoming of consciousness—is inaccessible to analysis while it occurs. It is immediate and pre-objective, flowing beneath the reach of introspection or language.

Thus, our comprehension of Self Fusion is always after the fact. We study not the flame, but the ash. Yet, in understanding this fusion, we approach a deeper insight: that subjectivity is not merely a function of the brain or body, but an event—a fusion of infinite potential (entropy), moral architecture (narrative form), and symbolic content (personal story). Only together do these form the intelligible “self.”

Narrative Cosmology as the Production of Cognitive Schemas

Immanuel Kant, in the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), writes:

“Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and the more steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”

Within the framework of Axiomatology, this duality expresses the very architecture of consciousness creation—infinity conceptualized into finitude. The awe of the infinite cosmos and the structure of moral reasoning within are not separate reflections, but the dual poles of the same existential operation. Their fusion enables the human being to uniquely transform raw, chaotic entropy into an actionable, meaningful blueprint for existence.

To elaborate this model, consider the metaphor of a computer system:

The internet connection represents entropy inflow—pure, unstructured potential.

The hardware is the narrative architecture that allows for structured subjectivity.

The software is the actual story: the mythic, symbolic, or cognitive schema that interprets and channels the flow.

Many people fail to intuitively grasp that stories are not optional; they are mandatory operating systems. Their nature and quality may differ—from religious myth to consumer propaganda—but a functioning human being cannot act in the world without some form of story structuring the inflow of entropy into behavior. Even the most mundane everyday tasks require a basic narrative scaffold to bind meaning to action.

How does this framework relate to Kant’s formulation? The “moral law within” is not just a set of ethical constraints; it is the internalized structuring force that makes the individual capable of self-governance. The capacity to produce cognitive schemas—mental frameworks that enable perception, judgment, and action—is rooted in this fusion of narrative structure and entropy regulation.

What is often misunderstood is the assumption that moral decisions arise in isolated moments of choice. According to process theory, by the time a person reaches a moment of apparent moral decision, the occasion has already been shaped by a complex constellation of prehensions—conceptual, physical, and moral—that predispose the agent toward a specific outcome. The actual decision is simply the final crystallization of that process.

According to Axiomatology, moral prehensions within every occasion are composed of two distinct but interacting layers:

The Will of God (WOG) – representing the spirit of the law, akin to Whitehead’s concept of the Initial Aim—a transcendental moral pull aligned with universal order.

Structured Internal Value Hierarchy (SIVH) – the letter of the law, the internalized and hierarchically organized moral structure of the individual, which may, at times, override the WOG.

This interaction means that the WOG, while universally present, is not determinative. It can be suppressed or overruled by the subjective moral architecture of the person—their SIVH—thereby producing an alternate cognitive schema for the occasion in question. This schema then functions in tandem with the conceptual and physical prehensions to form the basis for action or inaction.

In this way, narrative cosmology becomes not merely a poetic or mythic tool, but the deep, operative logic by which cognitive schemas are produced, moral orientation is enacted, and human consciousness becomes behaviorally intelligible.

The Nest of Moral Absolutes

When it comes to the “software” operating within the consciousness architecture—namely, the stories we internalize—these stories are not merely entertainments or symbolic devices. They serve as navigational instruments, guiding us toward moral absolutes. If the stories one adopts lack such absolutes—if they are narratively vague, morally ambivalent, or aesthetically captivating but ethically hollow—then their utility during moments of existential or moral crisis is negligible. A narrative structure that fails to provide vertical alignment offers no true anchor in the storm.

To clarify: if the most dominant stories absorbed into a person’s internal system are themselves relativistic or postmodern in orientation—championing vague values such as “acceptance,” “flow,” or “freedom” without hierarchical grounding—then the resulting Structured Internal Value Hierarchy (SIVH) will be just as diffuse. Such hierarchies often place the self or emotional comfort at the apex, leading to ego-centric decision-making disguised as moral freedom. In times of crisis, these stories offer no commanding direction—only the illusion of movement.

How do such stories enter our lives? More often than not, we do not find these stories—they find us. Their appearance is frequently conditioned by geography, culture, language, and chance exposure. Whether it is Homer’s Odyssey, the Bhagavad Gita, the Qur’an, or the Gospels, people encounter particular stories long before they consciously select them. But the determinative factor in how stories shape moral architecture is not their religious label, nor their cultural origin—it is their commitment to moral absolutes.

What determines whether a story can affect the SIVH long-term is not whether it is labeled as Christian, Islamic, or Hindu, but whether it embeds within its arc a non-negotiable vertical structure—a principle or Absolute that governs meaning, action, and sacrifice. When a story lacks this, its power to orient a person diminishes. However, for a story to effectively induct a moral absolute, it must be interpreted correctly within the larger narrative framework it belongs to. Misreading isolated elements or allegories can lead not to virtue, but to distortion. One must understand the story within the corpus of its greater whole. Otherwise, the “lesson” becomes fragmented and, ironically, relativistic.

Thus, the nest of moral absolutes is not found in the mere memorization of sacred tales or symbolic myths. It emerges when those stories are understood structurally, interpreted holistically, and internalized existentially—becoming not just narratives we admire, but value scaffolds we live by.

Bible as an Example of Stories in the Narrative Sense

When it comes to narrative-rich frameworks capable of containing and directing the entropy of pure consciousness, the Bible stands out as the most enduring and reliable corpus. It offers not merely a collection of historical or theological texts but a composite narrative system that can be internalized to structure moral meaning. However, its very richness also makes it easy to misinterpret, especially when approached superficially or in fragmented ways.

This kind of reductive engagement leads many to see the Bible as an “old book,” perhaps useful in a distant cultural or historical context, but irrelevant to modern existential questions. Worse, such an approach allows for dangerous misreadings—for example, the belief in “deathbed redemption” without genuine repentance, or the repeated assertion that “only God can judge,” deployed not as a theological truth but as a rhetorical shield against moral accountability. Another common distortion involves the idea that “every sin will be forgiven,” extracted from its wider theological context and weaponized to justify ongoing vice.

To properly grasp the Bible’s role as a narrative system embedded with moral absolutes, one must move beyond isolated verses or individual commandments. Yes, even children and adolescents in many cultures are familiar with the Ten Commandments, and indeed, many legal systems in the West draw foundational principles from them—prohibitions against murder, theft, adultery, false testimony, and so on. These moral laws reflect widely shared, intuitive boundaries necessary for any stable society.

However, if we aim to understand the deeper guiding principles embedded within the biblical narrative—those that can actively shape Structured Internal Value Hierarchies (SIVHs)—a holistic approach is essential. The Bible is not a legal code or a moral checklist. It is a narrative cosmos: a landscape of human suffering, betrayal, covenant, sacrifice, hope, and divine judgment. The moral absolutes emerge not merely as commands, but through the story arcs themselves—Cain and Abel, Job, David and Bathsheba, the Exodus, the crucifixion of Christ. Each story is not a standalone tale, but a moral vector pointing toward vertical alignment with divine order.

Therefore, the Bible is not just a book about God or morality—it is a narrative embodiment of cosmic logic. When rightly interpreted, its stories provide the necessary “software” that helps individuals channel the overwhelming influx of consciousness into structured, meaningful life paths. But without moral absolutes and contextual integrity, the text ceases to be transformational and becomes merely rhetorical. Aesthetic admiration without ethical submission leads nowhere.

The Guiding Idea Throughout Biblical Stories

When it comes to the entire biblical corpus and the moral absolutes embedded within it, one of the most illuminating moments occurs when Jesus is challenged to summarize the hierarchy of all commandments. In Matthew 22:36–40, Jesus is asked:

“Teacher, which is the great commandment in the Law?”

And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.”

This scene does far more than simplify religious obligation. The first commandment, often read too quickly, contains a profound vertical alignment principle: love of God with entire being—heart, soul, and mind. The second commandment, which appears horizontal, is structurally dependent on the first. Without the proper orientation toward the divine, the ethical relationship with others lacks foundation. In other words, horizontal morality (love of neighbor) is only stable when it rests upon vertical fidelity (love of God).

Together, these two commandments encapsulate the entire Mosaic law, which traditionally includes 613 commandments (known as the Taryag Mitzvot) drawn from the Torah—the foundational legal and moral structure of Judaism. At first glance, such a sweeping condensation might appear overly simplistic. But upon closer examination, we find that the commandments concerning ritual purity, social ethics, and personal morality all radiate from these two central directives.

This dual structure—alignment with the Absolute, and extension of that alignment into ethical behavior—serves as a metaphysical and moral cornerstone not only of biblical religion but of Axiomatology itself. Without a transcendent anchor (God), moral obligation becomes relativistic or utilitarian. Without moral extension to others, devotion becomes self-referential or ritualistic. Thus, both commandments are necessary, but the order matters: the vertical precedes and enables the horizontal.

What Does “You Shall Love the Lord Your God with All Your Heart, All Your Soul, and All Your Mind” Mean?

This commandment carries three profound implications: hierarchical vertical alignment, unity of being, and active participation.

Hierarchical Vertical Alignment

First, it asserts an uncompromising hierarchical alignment with one concrete, monotheistic, and singular God—the foundational claim of Christianity. Built into this declaration is a radical exclusivity: all your attention, all your devotion, all your existential orientation is to be directed toward one God only. There is no suggestion of multiplicity, plurality, or tolerance for alternative divinities. This is not a democratic theology—it is a metaphysical monarchy.

At the heart of this command is the idea of vertical alignment: there is someone higher than you, a transcendent moral authority to whom you freely submit. Your life, once aligned with this command, is no longer centered on yourself—it becomes oriented toward the Divine. This is not mere obedience; it is willing submission into a relationship of moral responsibility, entered into with the intention to serve.

Each component of the triad—heart, soul, and mind—is deliberate and loaded with meaning. The heart symbolizes your drives, emotions, and passions. These are not to be dismissed, but redirected—submitted to God. The soul signifies your existential commitment—your very being and trajectory in life. And the mind points to your rational faculties, your capacity for discernment, judgment, and truth-seeking. Christianity is unique in its insistence that all three—feeling, being, and thinking—must be harmonized and vertically aligned with the divine.

No other major religion articulates this holistic command quite so explicitly. While Islam similarly emphasizes submission to Allah, it often does so through legal obedience more than relational love. In contrast, Christianity demands love as the primary mode of submission—modeled by the life and sacrificial example of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. He is not merely a prophet or teacher, but the concrete, incarnate archetype of what vertical alignment looks like in human form.

Unity, Not Plurality

The second essential idea embedded in the commandment is unity of the self. To love God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind presupposes that you exist as a unified being—not as a fragmented multitude. Identity, in this context, is not endlessly malleable. It is not fluid, pluralistic, or contingent upon feelings, moods, or social constructs. Instead, the command assumes an integrated personhood—a coherence between thought, will, and desire.

This concept is vividly illustrated in Mark 5:1–9, where Jesus encounters a man with an unclean spirit. When asked his name, the man replies: “My name is Legion, for we are many.” Here, Legion is a profound expression of internal fragmentation—a psyche broken into parts, lacking centeredness or moral direction. Such multiplicity is not celebrated but cast out.

Vertical alignment with God presupposes that the one at the bottom end of the axis is also one. The self must stand as a singular entity—not many selves in conflict, but one self in covenant. Your past selves, present self, and envisioned future self must all be brought into alignment. Your identity cannot be reinvented on whim or whimsy—it must be owned, integrated, and sanctified. There can be no true submission to God without first achieving self-unity.

Active Participation

Thirdly, love in this biblical commandment is not passive. It is not about emotional assent, acceptance, or an effortless state of “flow.” It is active struggle. To love God is to take up a vocation—to respond to a calling that demands sacrifice, discipline, and daily dedication. It is not a moment of feeling, but a lifetime of action.

As Luke 9:23 says: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me.” This is the essence of Christian participation in divine order: not abstract belief or momentary euphoria, but daily carrying of the cross—the burdens, responsibilities, and sacrifices that come with aligning oneself to the higher will.

This path offers no promise of hedonistic comfort, personal entertainment, or unlimited self-expression. Those may occur as byproducts—but never as the aim. The core message is clear: pleasure, variety, and self-fulfillment can never occupy the top of the value hierarchy. The top belongs to God alone. Everything else must follow in submission.

To love God, therefore, is not simply to believe in Him—it is to serve Him with the whole of one’s life, actively and continuously. It is to sacrifice the ego, deny the fleeting passions of the moment, and orient oneself toward the eternal. That is the definition of moral alignment, and the foundation of Christian metaphysics.

The Horizontal Axis: “You Shall Love Your Neighbor as Yourself”

If the first commandment establishes the vertical axis, this second commandment forms the horizontal—together, they create the structure of the cross. The vertical dimension centers on alignment with God; the horizontal expresses that alignment through moral action toward others. The symbolism is not coincidental—it is structural. The Christian life exists at the intersection of transcendence and immanence.

“You shall love your neighbor as yourself” is not a call to passive tolerance or mere emotional warmth. It is, again, a demand for active love—a sacrificial commitment to the well-being and moral dignity of others. We are not told to merely accept our neighbor or to offer help only when asked. We are called to pursue their good as if it were our own—to mirror the same intensity of care, concern, and investment that we give to our own flourishing.

In theological terms, if the first commandment roots us in divine worship—offering ourselves to something higher—then the second commandment directs that offering toward the world. It is the outpouring of vertical alignment into horizontal sacrifice. Love of neighbor, in this sense, is not optional. It is the test of whether our love for God is real. And crucially, it can only be practiced in community. There is no solitary version of this commandment. The vertical must descend into the horizontal, or else it becomes a form of spiritual narcissism.

The Bible as One of the Best Sources for Narrative Cosmology

When we analyze the concept of Narrative Cosmology, it becomes clear that the Bible aligns exceptionally well with its structural principles. It contains a vast array of stories that do not merely entertain or inform but serve as containers for moral structure, providing the architecture necessary to frame and regulate the inflow of consciousness. These narratives—often mystical, emotionally profound, and theologically complex—demonstrate precisely how consciousness, when left unframed by moral absolutes, can spiral into disorder. This is vividly portrayed in the story of Cain and Abel, where unstructured emotion, envy, and failure to submit to divine hierarchy result in cold-blooded murder—the first narrative depiction of Cainian collapse.

The alleged conflict between moral absolutes, such as "do not kill" and "serve only one God," is addressed head-on in the story of Abraham and Isaac. This narrative clarifies a central feature of Narrative Cosmology: when values appear to conflict, hierarchical submission to God’s will—loving Him with heart, soul, and mind—trumps all else. In this case, the sacrifice of one’s most beloved (Isaac) under divine command reveals that even the commandment "do not kill" can be relativized under higher-order absolutes. This hierarchy is not arbitrary—it is structured. As Kierkegaardfamously argued, Abraham’s leap of faith is not irrational overthinking but a radical trust in the divine value hierarchy. Some absolutes are more absolute than others.

The same hierarchical structure emerges in the story of Job, where unbearable suffering and existential uncertainty are not resolved through reason alone but through steadfast submission to divine authority. As entropy increases—chaos, illness, betrayal—Job’s only path forward is to deepen his hierarchical sacrifice, anchoring his suffering in faith. This is not theological sentiment—it is the mechanics of Narrative Cosmology, functioning as a psychological and metaphysical framework. And in this sense, the Bible is not merely compatible with Narrative Cosmology—it is one of its richest and most enduring manifestations.